Violence is a Formation Issue

Violence is on my mind these days.

The truth is that I like to fight. If you asked me, I would say I love peace, but that’s often not where my body goes first. In fact, throughout the years I’ve harbored secret thoughts about settling disputes with fistfights, man to man. Or I fantasize that someone would provoke or threaten me to the point that I must respond or defend physically.

As an adult, I’ve never acted on my secret thoughts (no pastor who cares about his image would do such a thing, right?). And no one has ever threatened me with violence. Yet down in my gut, somewhere beneath my better judgment, is the instinct to use force.

I have assumed that I can be a person of peace and at the same time be a person fully prepared to exercise force. Peace in my heart and on my tongue, but violence in my body. Mr. Miyagi could pull it off, right? Is it really possible to cultivate both?

Is it really possible to cultivate both peace and violence? Share on XOn the brink of violence

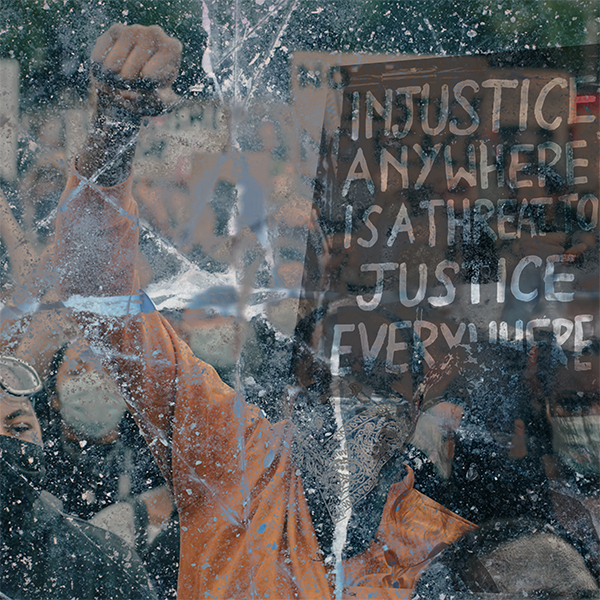

Violence is also on my mind these days because it feels like we live in a world filled with it. Indeed, it feels like we are a world on the brink, not just locally, but also globally. Millions suffer under violence, and recently the United States has responded to that violence with violent force, presumably with the intent to deter more violence.

When it comes to discerning how Christians ought to engage violence, this is the point where the conversation often picks up—at the point of present conflict. Wouldn’t you do something if you could? That’s the question that presses the issue.

Often, the Christian posture toward violence pivots around a question like this at this point, or the agenda gets set by a similar hypothetical.

What if, out of nowhere, a bad person is threatening my family with some type of imminent attack, wouldn’t I do everything I could to stop this bad person? If that bad person is threatening violent force to harm those I love, wouldn’t I use violent force in order defend my family? Wouldn’t I match force with force to deter the attack?**

These what-if scenarios are unhelpful for me because the point at which the question is pressed feels too far down stream to yield a helpful response. When confronted with these scenarios, I want to ask, “How did we get here?”

“How is it that I have the capacity to match force with force and be a meaningful deterrent? Where did I get the skills, the physical wherewithal, to stop or overpower the bad person?”

Then when I sober up from my masculine martial arts fantasies, I answer those questions. To be dangerous, I would have to have training. I wouldn’t get there by accident.

Muscle memory and the heart

Forceful responses that are meaningful deterrents are instinct-level skills. They’re bodily reflexes that are learned (that is, embedded in my body) through specific, thorough, and ongoing training. I would have to give myself unto a process of formation in order to train myself.

In a similar way, that process of formation and training also applies on the corporate scale. The acquisition and development of military might come by a long, thorough process of training. It comes along a deliberate, specific trajectory, not by accident.

What this answer reveals to me is that violence is fundamentally and foremost a formation issue. And, of course, not all formations are equally righteous. Violent force, even the kind meant to be a deterrent, is not simply a neutral action I choose from a set of equally accessible options, as if at any given moment I am as bent toward peaceful, non-violent action as I am toward violent force and retribution.

Just as I cannot simply choose virtue when I want to be virtuous, the choice between peace and violence does not happen like I might assume (i.e. I can simply will myself to act peacefully). Rather, I will respond out of what is “stored up in my heart,” as Jesus said. My body always shows the fruit of my training.

Thus, my answer to the “what-now” and “what-if” scenarios reveals more about the kind of formation I’ve undergone than it does how to walk in the way of Jesus regarding violence. My body will always tell the truth about which formation I’ve given myself unto.

It’s becoming clear to me that the way of violence and the way of peace are distinct and incompatible paths of formation. To choose one is not to choose the other. In fact, I think Jesus is clear that I cannot choose both ways. This is an implication of the kingdom reality that I cannot serve two masters; I cannot give myself unto the peaceful ways of God’s kingdom and the ways of violence and retribution.

Put another way, I cannot at the same time train my heart for peace but my body for war. This is simply not possible because bodily training is also heart training. The disciplines and postures that I habitually give myself unto shape my heart.

The bodily, even sacramental, dynamics at work here help explain why I can talk about peace, theological assent to peace, profess my love and preference for peace, and yet continue to find myself again and again in a fight. The disconnection between what I say and what I do with my body is a matter of formation and training.

For the earliest Christian communities, responding to violent aggression and force with violent aggression and force was inconceivable, partly because they did not have the physical wherewithal to assert a meaningful deterrent. And this wasn’t due simply to lack resources. It was a matter of training – a matter of the trajectory they were disciplined into. By matter of habit and training, they became the kinds of people who habitually made for peace – who learned in their bodies self-giving unto death.

So the question is (and this question must be asked before we get trapped too far “down stream”), What does it look like to become the kinds of people who reflexively, without having to stop and think, practice peace in distinction from those who, reflexively, without stopping to think, can match force with force?

Practicing the peace of Christ

This was the question Paul was inviting his churches to bring to bear in their lives. If we want to be people of Christ’s peace, people who participate in Christ’s resurrection life, then we must train ourselves in Christ’s peace.

If we want to be people of Christ’s peace, we must train ourselves in Christ’s peace. Share on X“Let us pursue what makes for peace and building up one another,” he writes in Romans 14:17. “Let the peace of Christ rule in your hearts, since as members of one body you were called to peace,” he exhorts the Colossian church (3:15). Again, this training in Christ’s peace is part and parcel of shedding the old life and putting on the new, becoming the righteous of Christ.

How can we give ourselves unto this discipline while clenching the sword?

In fact, this is where we can see how Jesus’ injunction to Peter to “put away your sword” becomes a pattern for all who would walk in Jesus’ Way. To “put away your sword” is not simply a circumstantial, provisional command, but a completely new discipline and posture for those trust Jesus as Lord.

**Author’s note: Roger Olson used a version of this “what-if” in a recent article, where he concluded that Christians could celebrate the bombing of Syria.