3 Formational Practices for Difficult Conversations Every Church Can Learn

Dr. Raleigh Washington, the president and CEO of Promise Keepers and spokesperson for racial reconciliation, often would pepper his talks with the catch phrase “not for guilt, just for understanding.”

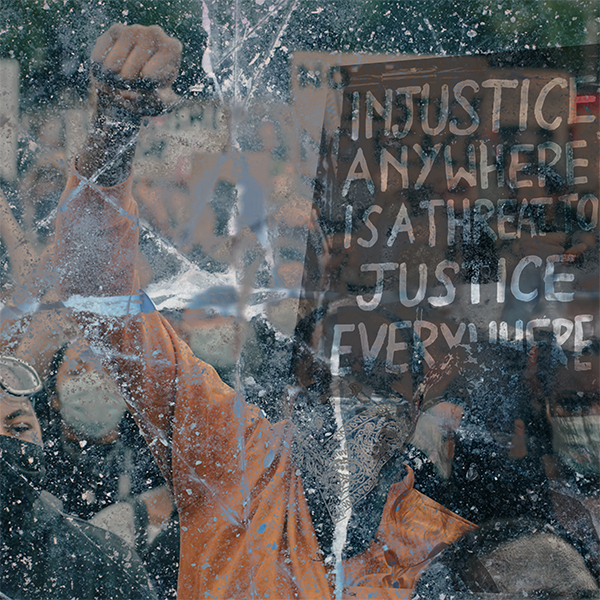

He was asking for a deeper listen than our normal tendency to close our minds and react when we hear something challenging or contrary to our thinking. He used this phrase often as he was having a difficult conversation with his audience about race.

Such conversations are often like walking through a minefield. Dr. Washington was inviting his audience to listen—without blowing up his character, intent, or facts before he made his point.

I want to have one of those conversations. I will be tiptoeing from sentence to sentence.

The phrase 'not for guilt, just for understanding' invited the audience to listen—before he made his point. Share on XLet’s Begin with What We Have in Common

I am a white, middle-class, educated woman who has privilege and access. I want to serve on the solution-side of racial justice, gender equity, and sexual preference conversations. I am passionate about leveling the playing field.

However, this is a messy journey, fraught with hidden minefields. So I wonder: do we have a common starting point?

If we don’t have a common starting point, it’s really difficult to find the way through the conversation before an explosion occurs. I would like to humbly suggest a starting point. I also want to suggest some formational behaviors that make that starting point real, and not just an ideal. I believe, then, more of these conversations might get to an explosion-free end.

Could it be that the common starting point is the shared platform of our humanity?

Before we are black or white, female or male, straight or gay, we are all 100% human. Productive conversations begin with that truth because it means we acknowledge our human frailties. We are not the gods. We are God’s people. If we cannot start at this point, how do we move forward when the frailties erupt with anger, rigidness, fear, or self-righteousness?

If there is judgment before the conversation even starts, we don’t ever really start. Rigid judgements happen when we become the “saviors” and have no need of one.

So let’s begin here: We are first—no matter what—part of the large and diverse human family. There is not one who is more human than the other. There is not one more preferred than the other. Even if the iceberg were flipped and the privileged and powerful were on the bottom and the rest of humanity on top, God still loves the entire iceberg and sent his only Son to redeem us. The Son came to set us free from our need to be “as gods.”

It is also not just the individual humans. Systemic evil is pervasive. Systems of power and control thread through every fabric of our society. There is neither school, nor courtroom, nor grocery store, nor factory, nor family group that isn’t infected with the fallen human desire to control and to exclude. It is not the privilege of the few.

Anyone having experienced racial injustice, sexual harassment or rape, bullying, or betrayal and character assassination gets an extra, extra, measure of patience and understanding and empathy and justice, but no one gets a pass to be unkind.

A weaponized mouth increases trauma and does not lead to peace. Unrighteous anger[1], disgust, and hate are meant to hurt and destroy another human spirit. Such emotions subvert any efforts to deeper conversations with the Holy Spirit, within ourselves, and with each other.

If we can’t start with recognizing our common frailties as humans, it is an exercise in futility to start at all.

However, if we can agree to start at that place, then here are three formational practices that will ensure a better outcome for difficult conversations. These are derived from three small incidents involving Jesus, who models for us a way.

No one gets a pass to be unkind. @MaryKateMorse Share on XThree Practices to Form Us for Difficult Conversations

1. Create space for cool-down and reflection.

In Luke 4, Jesus is in Nazareth and stands up in the synagogue to read from Isaiah and Leviticus on the Sabbath. All are enthralled with him. In verse 22, they are speaking well of him. However, by verse 28, they are not. The crowd becomes enraged and intends to throw Jesus off a cliff and kill him.

But Jesus passes through their midst and goes his way.

In this instance, Jesus did not say or do anything—even though he could have.

Another place we see this is in Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness. Jesus commits not to “throw himself off a pinnacle” in order to prove who he is. You see—difficult conversations are not about proving, they are about listening. If passions are aroused, the conversation is over.

Therefore, when we are angry, when the blood pressure is up, and we’re on the verge of being out of control—walk away. Small fires can breed giant, uncontrollable conflagrations. If passions are aroused, cover it with quiet leave-taking.

2. Do your own inner work first.

The second incident is in Luke 9. Everything is going great. Jesus feeds 5,000 people and later, he is transfigured. In verse 43, everyone is marveling at all he is doing.

But then in verses 52-55, Jesus sends messengers to a Samaritan village to prepare for him. The messengers are turned away because Jesus is traveling to Jerusalem. James and John, two of his closest disciples, upon hearing this respond with, “Lord, do you want us to command fire to come down from heaven and consume them?”

James and John are so indignant and offended, they are willing to destroy an entire village of men, women, and children. This is the insanity of an irrational rage and puffed-up arrogance.

Jesus rebukes them.

Going back again to his temptation in the wilderness, Jesus commits not to satisfy short-term emotional and physical needs by taking things into his own hands. He does not turn the stones into bread.

My point is this: If your response to any issue is unrighteous anger, disgust, or hatred, then you have inner work to do first.

Spend time in prayer—as long as it takes, and it could take months—to know the source of your own unrighteous fire before you correct others. I think much of the time, most of us shouldn’t talk at all. We are so unaware of our own transgressing.

3. Embrace humility.

The third incident, also in Luke 9, finds the disciples arguing about who is the greatest. Taking a child, Jesus teaches them to choose the least place rather than the best. Trying to have the most status, most access, most power, most “rightness” will drive us to compete rather than connect. To become like a child, we give up our privilege to be in control.

In the desert, Jesus would not bow down to worship anything about the fallen one or the fallen way. Whenever our “rightness” or “righteousness” leads to unkindness, we give homage to both. Whenever we feel overwhelming urges to compete, conquer, or control, we are living out of our own pride and privilege.

Instead, let us take the place of the child and embrace humility.

Difficult Conversations Can be the Place We Welcome God’s Kingdom of Peace

How can we suppose that in our carnal, crowded, and arrogant human frame we can have a conversation with anyone different from ourselves and expect a good outcome?

Wouldn’t it be amazing if we had a quiet room during difficult conversations where anyone could go to pray and process when they become angry or fearful?

Wouldn’t it be amazing if we spent as much time processing our own anger and inner turmoil in prayer with the Spirit and with trusted guides as we do attacking and trying to control outcomes? We would all benefit from a working awareness of our own triggers and from taking ownership of our own “stuff.”

Wouldn’t it be amazing if we came with humility to a difficult conversation, resting in the truth that God is Sovereign and Wise, and we are not?

In doing these things, is it possible we could become persons of peace—like Jesus, the Lamb of God?

I think we can.

Is it possible we could become persons of peace—like Jesus, the Lamb of God? Share on XBut the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control; against such things there is not law. Now those who belong to Christ Jesus have crucified the flesh with its passions and desires. If we live by the Spirit, let us also walk by the Spirit. Let us not become boastful, challenging one another, envying one another. Gal. 5:22-25

[1] Righteous anger is the appropriate anger that compels us to address an injustice, and it always costs us something. Unrighteous anger drives us to hurt someone so we “feel better” and we “make them listen.”