For Kingdom Citizens, Civil Discourse Doesn’t Work

In this antagonistic era, we must look for a way to engage without destroying one another. But while the desire for a healthier vision for dialogue remains right and good, I want to propose that “civil discourse” is not a framework with enough imaginative power to dislodge us from violent rhetoric, to challenge the powers and principalities at work, and to make space for sharing in the humanity of others. Rather, for those who have been made citizens of God’s kingdom and members of Christ’s body, our dialogue is grounded in a vision for neighborly love—love that is both prophetic and radically self-giving.

The desire for a healthier vision for dialogue is good, and yet 'Civil discourse' is not a framework with enough imaginative power to dislodge us from violence or the powers and principalities at work. Share on XThe Problem with Civil Discourse

The idea of love of neighbor is not novel, of course. The point is that we are in a political moment where we need to name that neighborly love is not the same thing as civil discourse.

Naming the difference is important for shaping a distinct witness to how God is reconciling the world in Christ. Naming the difference helps Christians not get sucked into the vortex of a ‘lowest-common-denominator’ political vision that neuters the liberating power of the Gospel.

“Civil discourse” is often taken to mean that we need spaces where people don’t act and speak like jerks one to another. Civil discourse often means remaining polite, slowing a disagreement by a statement such as this: “Things are getting heated, let’s all calm down and not get too worked up.” At the very least, not being a jerk is a desirable goal. When our political imagination is grounded in a vision for social flourishing where the greatest good is allowing individuals to pursue self-interest, civil discourse is probably the best option.

But as citizens of God’s kingdom, we affirm a different vision for flourishing in community together. It is a vision where people actually belong to one another in Christ, and are freed from self-interest to pursue the flourishing of others. It is the vision of radical love and hospitality for neighbor, revealed most fully in Christ’s self-giving, prophetic action.

Civil discourse is not the best imaginative framework for framing Christian discourse because civil discourse is a category largely determined by a modern story in which the particular claims of Jesus’ Lordship are presumed to be inherently violent and dangerous to the formation of true social peace. True peace, the story goes, can only be achieved between us when we come together leaving behind our particular “religious” convictions.

So, the problem is that many Christians have either inappropriately embodied a discourse that is violent, antagonistic, and even colonizing, or they have capitulated to the notion that expressing particular convictions must be inherently violent and thus settled for dialogue where the particular, liberating, and prophetic vision of New Creation in Christ was not allowed at the table.

Civil discourse leaves us “talking nice” to one another, but in the pursuit of what end? What becomes of our disagreements in a world where the greatest good is the supposedly free pursuit of our self-interest?

What about when those disagreements go deeper than abstract concepts and the “color of the carpet” and have to do with real persons and the dehumanization of vulnerable, marginalized bodies?

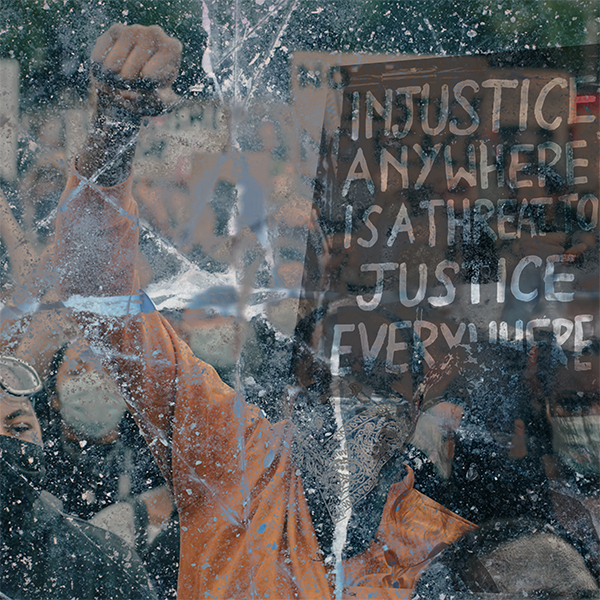

A major problem with “civil discourse” as a framework is that it tends to leave the existing broken systems unchallenged and thus perpetuates the pains and problems that are bubbling beneath heated dialogue. People who bring prophetic speech that challenges the status quo are often accused of threatening civility. Those in power who are knowingly or unknowingly responsible for oppression can thus use “civility” as a tool to silence prophetic voices.

As citizens of God’s kingdom, we affirm a different vision for flourishing in community together–a vision where people belong to one another in Christ, and are freed from self-interest to pursue the flourishing of others. Share on XWhat the Gospel Teaches Us: Neighborly Love That Disrupts

Rather, “neighborly love” is a better, thicker framework for dialogue by Christians with others because it makes space for both reconciliation and liberation in Christ. Several concepts spring to mind:

- Neighborly love compels me to steer clear of coercion when we disagree. The love for neighbor we learn from Jesus is self-giving love, overflowing from the gratuitous gift of life in Christ. As such, Christian discourse is not inherently violent or coercive toward those with whom we disagree. Our dialogue is grounded in the conviction that we have been made members of one another in Christ and are freed to love our neighbors, near or far, by pursuing their flourishing. This vision provides a better imaginative framework than the pseudo-peace achieved through an agreement not to get in each other’s way.

- Neighborly love is inherently prophetic. Dialogue marked by [self-giving] love of neighbor will sometimes cause offense and sound downright un-civil. Sometimes, the most faithful, neighbor-loving speech we can give is fundamentally uncivil because the civitas around us works against the civitas characteristic of Christ’s body, either by making idolatrous claims for our allegiance or by perpetuating systems that disfigure the image of God in certain persons.

Because it is oriented toward the humanization and liberation of persons, we should expect that our dialogue at times will provoke the powers and principalities embedded in the structures that dehumanize and work against God’s reconciliation in the world.

The love for neighbor we learn from Jesus is self-giving love, overflowing from the gratuitous gift of life in Christ. Our dialogue is grounded in the conviction that we have been made members of one another in Christ. Share on XSome Practical Guidance

What does a posture of neighborly love look like for our world today? A few thoughts.

When we come around the table to dialogue with others, especially those with whom we disagree:

- We don’t have to be the first to speak.

- We don’t have to have the last word.

- We don’t have to have the loudest voice.

- We don’t have to “win” an argument.

Instead, guided by neighborly, self-giving love:

- We can speak with others as fellow or potential members of Christ’s body.

- We can give honor and voice to the “weakest” member among us.

- We can ask questions that reveal desires and fears behind issues.

- We can speak prophetically by giving witness to how God’s reconciliation in Christ challenges the dehumanizing powers and principalities embedded in our personal habits as well as our social structures.

///

Because it is oriented toward the liberation of persons, we should expect that our dialogue will provoke the powers and principalities embedded in the structures that dehumanize and work against God's reconciliation in the world. Share on X