Preaching “the Black Stuff”

“I’d get a lot more out of your sermons if you didn’t preach all the black stuff.”

Phil and I weren’t close friends, but we were (and still are) acquaintances. Most importantly, he is white and, at that time, I, a black woman, was his pastor.

I can’t remember the rest of the conversation. I was caught off guard by the dismissive summary of the term “the black stuff.” Our congregation was a rapidly gentrifying church in a transitioning, urban neighborhood. Conversations with white folks uncomfortable with “the black stuff” were becoming the new normal. When the heat came in these conversations, usually in the form of angst or anger, I reflexively stepped behind my mental defense shield, a set of conciliatory auto-responses intended to communicate empathy and invite the “Phils” and “Phyllisses” of the congregation to more dialogue in the future.

Through Many Dangers, Toils, and Snares

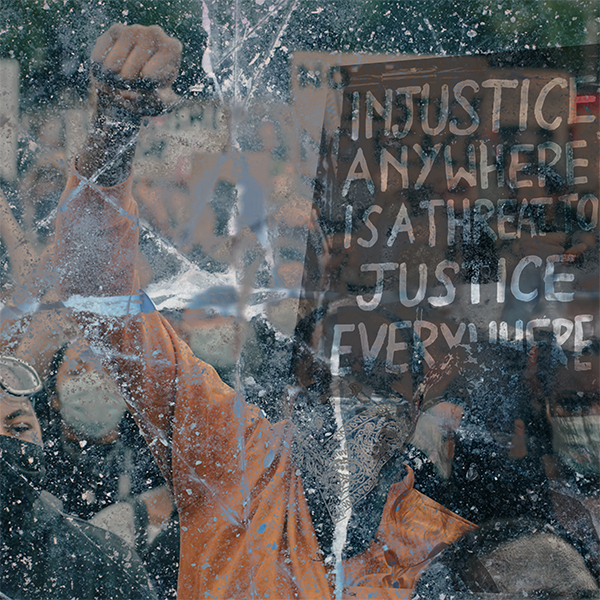

To be clear, what Phil called “the black stuff,” I understand to be the whole Gospel. Enslaved Africans in America understood that God’s command that Israel “stop the oppressor” (Isaiah 1:17) was both a word to Israel AND a word to them about the character of God. “Through many dangers, toils, and snares,” enslaved men and women whispered visions of justice and freedom to each other through the generations. It’s this Gospel message that animated the will of the black church and shaped the tradition of black preaching.

But colonists and slaveholders also whispered their version of a truncated Gospel down through the generations. Many of us with experience in the evangelical church are theological heirs to a simple story of battles fought and victories won, with the blessing of God. But the stories of suffering, survival, and the persistent pursuit of God among enslaved Africans and indigenous people have been cropped out of the picture many of us inherited. If you grew up with a cropped story, it’s hard to acknowledge that on the edges of your picture of colonial purity, victory, and blessing are black and indigenous bodies revealing more truth than you realize about the “One who saves.”

The stories of suffering, survival and the persistent pursuit of God among enslaved Africans and Indigenous people have been cropped out of the picture many of us inherited. Share on XHe told her, “Go, call your husband and come back.”

“I have no husband,” she replied. (Jn 4:16-17)

While we struggle to hide our embarrassing stories from each other and God, Jesus invites us to the kind of truth-telling that crushes the oppression of evil. In the story of Jesus meeting the Samaritan woman at the well, his response to her truncated truth is to tell her whole story:

Jesus said to her, “You are right when you say you have no husband. The fact is, you have had five husbands, and the man you now have is not your husband. What you have just said is quite true.” (Jn 4:17-18)

While most of us (including me) are tempted to see Jesus’s truth-telling in this story as a holy “clapback” or a “power move” to signify her lower, social status, it is, instead, an act of grace. This ostracized, shame-filled woman is at the well to get water at a time when she could be certain to avoid social interaction. But Jesus tells her messy story and sets her free to tell her whole town about the man who “told [her] everything [she] ever did.” The writer tells us that “Many of the Samaritans from that town believed in [Jesus] because of the woman’s testimony.” (Jn 4:39) The response to the woman’s messy story is freedom and grace, not only for her but for everyone around her, too.

The Whole, Messy Truth

Thankfully, Jesus not only knows the not-so-pretty parts of our personal stories but also the downright ugly parts of our systemic, generational histories. It’s been a few years since my conversation with Phil. Since then, I’ve come to understand that the fragility of some white folks, when hearing the truth of the Gospel from the voices of the oppressed, is an effort to cling to a neat and tidy Gospel story. But our neat and tidy Gospel stories won’t save us. So, this year, I’m preaching about “the black stuff” on purpose during Black History Month. It’s become my practice to preach about “the poor stuff,” “the indigenous stuff,” “the gender stuff,” and more—because all the “stuff” belongs to Jesus.

Whether you’re a preacher, teacher, or reader, I invite you to meet Jesus in the margins of your neat and tidy story. There you will find the Spirit of God is telling the whole, messy truth about you through the voices of the oppressed. There you will also find a healing grace to set you free to become an agent of freedom for those around you.