Forgiveness is Free…But Repentance Comes With a Cost

But Zacchaeus stood up and said to the Lord, “Look, Lord! Here and now I give half of my possessions to the poor, and if I have cheated anybody out of anything, I will pay back four times the amount.” (Lk 19:8)

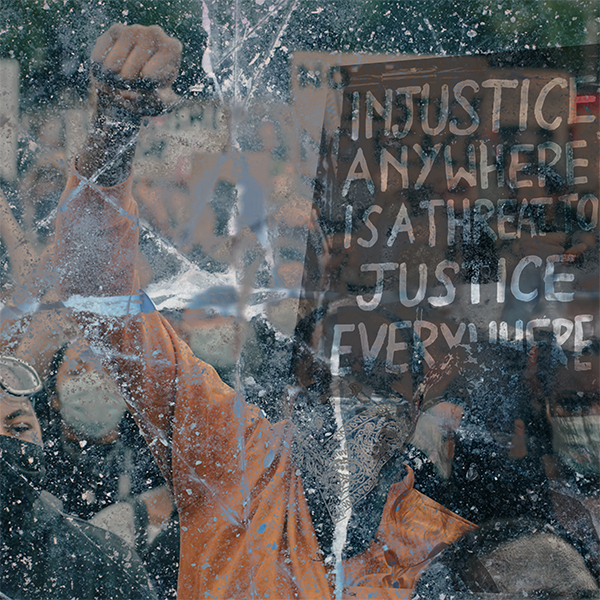

Five years ago, the world erupted in protests over the death of Eric Garner, a black man choked to death by a New York City police officer. I am a black pastor and a 20-year veteran leader in multiracial, Christian community. In the aftermath of Eric Garner’s death, I was given a myriad of opportunities to speak to white Christians who wanted to “listen and learn” about the realities of racism. I joined panel discussions with other black and brown Christian leaders, believing that transparency about our soul pain would inspire solidarity in those who told us they “really wanted to know.” I was wrong. Eventually, the fire of that moment faded. And white Christians, who were “listening and learning,” couldn’t sustain their newly-found passion for racial justice, even as violence against black Americans at the hands of the state continued.

Still Tired…

Five years and countless hashtags later—#sandrabland, #walterscott, #tamirrice, #altonsterling, and #philandocastile, to name a few—George Floyd’s murder set our cities and the world both literally and figuratively on fire. And once again, I’ve been invited by earnest, white Christians to speak at their “listening sessions” and to pray with them as they confess the sin of racism…again. But this time, I declined to attend. The large crowds in the streets, advocating for Black lives and pushing for change, tempt me to exchange my cautious skepticism for unfettered hope, but I can’t. At least where the church is concerned, I’ve seen this movie before.

Grieve, lament, repeat. This is the well-worn path of most white folks I’ve worked with in response to racial-injustice-turned-tragedy. Most grieve with the Black and Brown folks in their midst. Some cry out to God in lament, acknowledging both their blindness and helplessness in the face of institutional racism. But this, in my experience, is where the journey stops. So, forgive me if I don’t show up at the next “we want to make sure that the Black church knows we’re all in this together” rally. Because, honestly, I am tired. I’m tired of being expected by white Christians to be grateful for expressions of repentance rooted in a cheap grace that doesn’t take into account the true cost of racial injustice. I’m tired of hug-it-out reconciliation movements that bring us all together under the banner of unity for as long as the service lasts. It’s all good when we’re all together, but “when the music fades,” as the praise song goes, so does our accountability for loving our neighbors as ourselves.

I’m tired of being expected by white Christians to be grateful for expressions of repentance rooted in a cheap grace that doesn’t take into account the true cost of racial injustice. Share on XMore Than Grieving

The hard work of racial justice will call us all to more grieving and lamenting in the days and years ahead. But deepening our collective healing from our national sin will also require acts of repentance that include repair. Racism allowed white-bodied Christians to interpret their stolen land, stolen labor, and accumulating resources as gifts from God. Sermons and catechisms enshrined the inferiority of Black and indigenous bodies as a part of God’s original design. “Savage” Native people were destined for destruction and African “beasts” were only useful as labor. Present-day racial disparities in education, health care, housing, and criminal justice reflect the four centuries-long trajectories of power and resources away from Black bodies toward white bodies. This unjust advantage was passed from fathers and mothers to their sons and daughters. Whether white-bodied Christians today are intentionally or unintentionally caught up in benefiting from this sinful enterprise, repentance from generational sins still requires repair.

Racism allowed white-bodied Christians to interpret their stolen land, stolen labor, and accumulating resources as gifts from God. Share on XHere’s where Zacchaeus, that wee, little tax collector and thief, can point the way. That is, if the church will let him speak, not just as a children’s story, but as someone with a testimony about what happens when the grace of God comes to your house for dinner. It should be noted that Zacchaeus repented with acts of both charity (“I give half of my possessions to the poor”) and justice (“I will pay back four times the amount”). In this story, the taste of love and grace Zacchaeus receives proves to be better than the power and material possessions he’s amassed. His repentance is a whole-life response to the Good News.

What does whole-life repentance from racial injustice look like in your neighborhood? Your church? Your denomination? Whatever the specifics repentance toward justice will include practices of white folks letting go of both material resources and the power to decide how those resources should be used. The truth of God’s grace means that we can all look closely at the terrible things that have been done in the name of white supremacy, because forgiveness is real. Forgiveness, for all of us now and the generations then, has always been free. But the repentance that leads to freedom for all of us, the kind of freedom that creates joy in the streets—that kind of repentance has a cost.

Editor’s note: The path of communal repentance is an invitation for your church to engage your Black and Brown neighbors in a deeper way. Please contact Leeann (leeannryounger@gmail.com) if you’re a leader interested in discussing how this might look in your context.