Biblical Interpretation and Leaning into the Mystery of God, Part 1

I’ve heard of a play on Isaac Newton’s famous expression “standing on the shoulders of giants” that says we actually stand on top of many regularly-sized human beings all stacked up. Such a quip feels like the appropriate opening to a reflection upon the nature of epistemology and its relation to biblical interpretation. I am indeed a very small man, who, if positioned in any way to see beyond myself, is only so afforded by the broader, sometimes bruised shoulders of others.

Much of the age-old tension in the church around the topic of biblical interpretation springs from a few terribly familiar and riveted patterns of dialogue. What is often referred to as biblical scholarship today is actually not the result of fresh contemporary discussion but rather recurrent, dogmatic, and uninspiring, gavel-blows leveled by figures who are content simply to fortify their own denominational bulwarks.

Much of the age-old tension in the church around the topic of biblical interpretation springs from a few terribly familiar and riveted patterns of dialogue. Share on XMy contention will not be with any of the deductions drawn from particular theological traditions but with the process itself by which we have naively, yet callously, all but eliminated the practice of humble, inter-denominational discourse. It is not the possibility of disagreement that I wish to amend, but the soil from which the weeds spring, for every gardener worth his or her salt knows that healthy soil equals healthy plants.

Polemical Patterns in Politics and Pulpits

We can all relate to the frustration of hearing the same argument said a thousand times only with increasing intensity, as if to affirm some implicit truth that to argue a point louder than one’s enemy (or brother) somehow makes it correct.

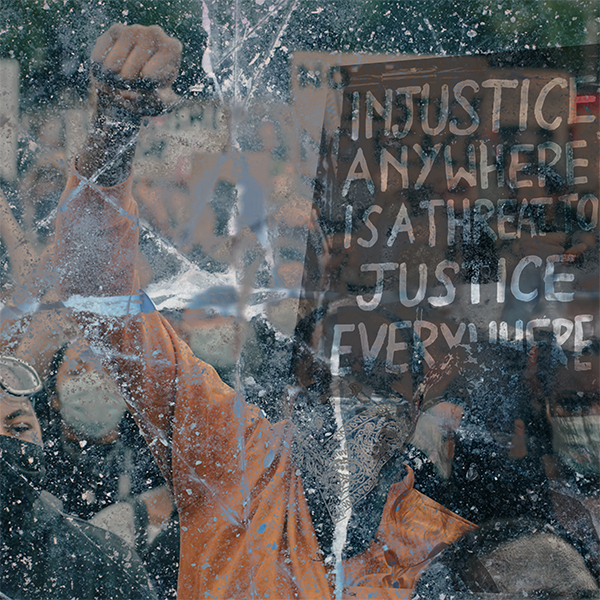

I wrote last year that the recent US political landscape has most clearly illustrated the present alarm in my own heart toward the disappearing practice of safe, altruistic, and effective dialogue. It goes without saying that what we witnessed throughout the Trump presidency, much of which was drawn out by the contentious character of the former president, is evidence of a hardened bi-partisan divide that seems no longer capable of performing courteous and empathetic conversation.

The televised debates, among other embarrassing blunders, highlighted a more damning reality than the policies either side espoused (believe it or not)—the utter ineptitude of most Americans to stand within the friction of abrasive and unsettling conjecture with enough fortitude to underscore even the value of the convention itself (let alone arrive at an agreeable conclusion).

I proposed that such behavior would only help to further dismantle the very memory and experience of mutual trust and empathy between persons and communities, eventually eroding away the very environment necessary to bring forth, challenge, and agree upon truth. Many of our political leaders modeled (and even called virtuous) behavior and rhetoric that was barbaric and dehumanizing, behavior and rhetoric that irretrievably reduced the collective capacity of a watching nation to both believe in the value of and perform respectable interchange.

In my own estimation, we remain not far from witnessing and participating in the collapse of one of the key societal underpinnings upon which our nation was built, and upon which human history has roundly depended. But, what do I mean by collapse? I define collapse as the arrival of a widespread and irreversible disintegration of human interaction where gentleness and other cozy sentiments become an afterthought altogether—antiquated terms with no room for expression in a world so atrophied in the practice of genuine human interaction. A world in which experience has so thoroughly taught us to trust nothing and no one and to believe only in the purity of our own epistemology would inevitably reduce us to the lazy and heinous exercise of categorizing entire groups of people and ideas based on the slightest of innuendos. This is a very real experience already for some, and I do mean within the Christian church. What grows out of this wasteland, I dare not imagine.

We remain not far from witnessing and participating in the collapse of one of the key societal underpinnings upon which our nation was built, and upon which human history has roundly depended. Share on XPolitically speaking, one could articulate this simply as the loss of authentically democratic dialogue. Within the church, the deeper appeal must be to the environment of humility and trust authored by God’s Spirit and love.

Without a warming of our hearts and minds to the vitality of fraternity and fellowship that surrounds such dialogue, we will fail to circumvent the exhausted patterns of recent generations who at times have been so fearful of their own invisible assumptions that they’ve forgotten the supreme doctrine of the church, the doctrine of love. Love, I suggest, is both the appropriate and adequate medium by which we must steward our epistemological and hermeneutical efforts.

Humility and Trust for the Task At Hand

BIblical interpretation, also called hermeneutics, is a core discipline of the church. All churches who affirm the basic tenets of historic Christianity defend the centrality of the inspired canon as the authoritative written witness to our corporate life and faith. It sufficiently directs us to the authority of God who has expressed his divine will to human agents throughout history, culminating in the perfect and final revelation of Jesus Christ, God’s own Son. The members of the church who wrote the Holy Scriptures by inspiration of God’s Spirit is the same church that must now rely on the same Spirit to rightly appropriate and articulate the Scripture within the present.

So, what’s the challenge?

Human agency has always been necessary for both the writing and interpretation of Scripture. This was by God’s design. As much as we may wish otherwise, the Bible did not fall out of the sky. It is a product of cooperation between divinely selected but contextually-bound human vessels and the Holy Spirit.

The Bible did not fall out of the sky. It is a product of cooperation between divinely selected but contextually-bound human vessels and the Holy Spirit. Share on XAdditionally, as it did not originate in a vacuum, the Bible is similarly not interpreted within one. Biblical interpretation is as waylaid by contextual variables as any other ancient text, both on the side of the author as well as the interpreter. Even those who affirm the inerrancy of Scripture cannot argue for interpretation or application that is free of user error. No interpreter, no matter how illuminated, receives a perfect download. This is a complication for which we collectively bear the weight, and I will contend that it doesn’t have to pit us against one another like it so often has.

In Part 2 of this article which will release on Friday, I will offer suggestions on how we are to shape our hermeneutics by strengthening certain convictions, while softening others, all while drawing us into an honest and mutual awareness of the difficulty before us and the humility and reverence that is thus required when going about such work.