When the Psalm Isn’t For Me

What does it say?

What does it mean?

What does it mean for me?

What is God calling me to do in response?

These simple questions have guided Christians to understand the Bible as God’s word not only in an abstract but in a deeply personal sense. It is God’s word for me, calling me to do something in response. And when it isn’t clear that the words I’ve read have immediate implications for my current circumstances, I am inclined to either move on to more “relevant” passages or to dig deeper for the personal meaning.

When it comes to the Psalms, that personal meaning is often a spiritual meaning. Rich physical descriptions, visceral language, and human actions are stripped of their literal meaning to become spiritual metaphors for whatever my current circumstances happen to be. The desert is my dry soul; the thirst is my desire for Christ; the satisfied hunger is spiritual contentment.

No doubt there is a place for this spiritual meaning. But in the quest for personal application, we risk missing the physicality of the Psalms and the way they describe the real circumstances of real people, past and present. We risk missing the opportunity to recognize that the Word of God is also for others.

In the quest for personal application, we risk missing the physicality of the Psalms and the way they describe the real circumstances of real people, past and present. Share on XLike many people around the world, I’ve been focused on the news of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. I’ve checked social media for posts from friends in the region. I’ve taken time in class to answer my students’ questions about what is happening. As a church historian with some expertise in Eastern Europe, I’ve attempted to locate current events in their historical, political, and ecclesiological context. I’ve prayed for my friends, for their families, for peace.

But my American Christianity inclines me toward personal application, toward action, toward doing something. I want to know where to donate, who to call, what to say. And when it isn’t clear what my personal action step is, or when the enormity of the situation makes my action seem ineffectual, I risk disengaging. It becomes easier to retreat than to live with impotence. What does it mean for me? What is God calling me to do in response?

What if those are the wrong questions to ask as images of toddlers in basements and people weeping at bus depots race across the screen? What if it isn’t about what I can do?

My personalized, spiritualized, action-oriented interpretive instincts collide with the historical and contemporary reality of Psalm 107:4-9 (NRSV):

Some wandered in desert wastes, finding no way to an inhabited town;

hungry and thirsty, their soul fainted within them.

Then they cried to the LORD in their trouble, and he delivered them from their distress;

he led them by a straight way, until they reached an inhabited town.

Let them thank the Lord for his steadfast love,

for his wonderful works to humankind.

For he satisfies the thirsty, and the hungry he fills with good things.

These words are not an allegory for the state of my soul. They are a description of the condition of real people’s physical circumstances—whether the Israelites seeking deliverance or the Ukrainians seeking refuge or untold millions of others who have wandered, hungry and thirsty, seeking a town where they can receive shelter and comfort. These words are the historical account and contemporary promise of God’s intervention, not only for peoples’ parched souls but for their hungry and endangered bodies.

We cannot escape the world. If in turning to Scripture or to prayer we seek a moment of retreat and reprieve from the distressing news of the day, God in his great mercy might use the prayers of the Israelites to re-ground us in reality. The Psalms are not only a stream for our spiritual deserts. They are an invitation to encounter the presence and promise of God in the visceral reality of the physical world, here and now. They are an invitation away from our spiritualized and personalized hermeneutic and an entry into the distress of the suffering.

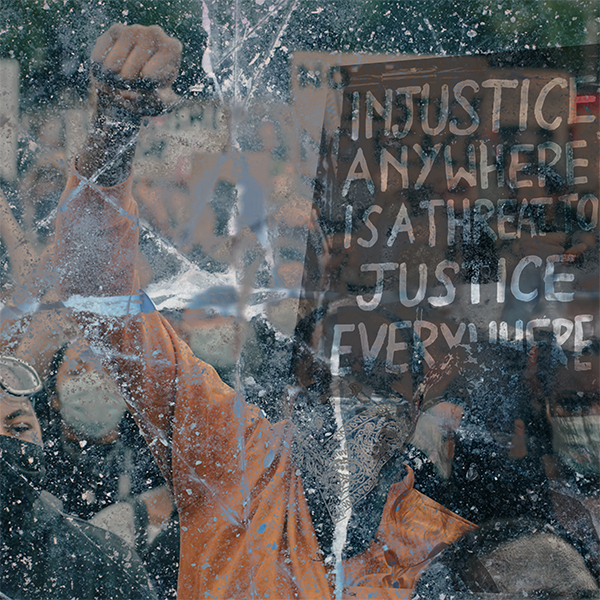

The Psalms are not only a stream for our spiritual deserts. ... They are an invitation away from our spiritualized and personalized hermeneutic and an entry into the distress of the suffering. Share on XThe Psalms are not our escape; they are our entrance. They give us the words to enter into the pain and the assurance that God is not distant from distress. They release us from ourselves and free us for others. We are freed to pray the Psalms for others, freed from seeking our personal spiritual meaning, so we can pray that Ukrainians walking toward borders find inhabited towns and that soldiers in distress find aid. We are freed from the apathy, complacency, and escapism that threaten when our actions seem too small; we are freed from the self-centered approach to Scripture that tells us every word is for us. We are freed to see the tear-streaked faces of those fleeing Kyiv and Kharkiv and Kherson and Lviv and to speak the words of God’s presence and promises for them.

The Psalms are not our escape; they are our entrance. ... We are freed to pray the Psalms for others, freed from seeking our personal spiritual meaning, so we can pray that Ukrainians walking toward borders find inhabited towns ... Share on XThen they cried to the LORD in their trouble, and he delivered them from their distress (Psalm 107:6, NRSV).