Christian Nationalism: What Defines It

A few summers ago, while heading home to Chicago from a day at the lakeshore, our family was driving along a quiet road in Indiana when something caught my eye. I slowed down, made a quick U-turn, and pulled up alongside a small house set back from the road. There, a few feet from the blacktop, was a homemade billboard facing our idling car. Its bright, patriotic colors are what had drawn my attention. Peering through the windows, our family took in the sign’s many messages trumpeting the dangers of the political left and proclaiming God’s favor over a Christian nation. There was an angry, almost violent tone to the whole display. We don’t see much of this sort of thing in our predictably blue city; the roadside signs that pop up every few years in our neighborhood aren’t nearly as creative and generally leave God out of the political equation. At the time, I filed our quick detour away as a quirky expression of political folk art, a window into a minority perspective and not much more.

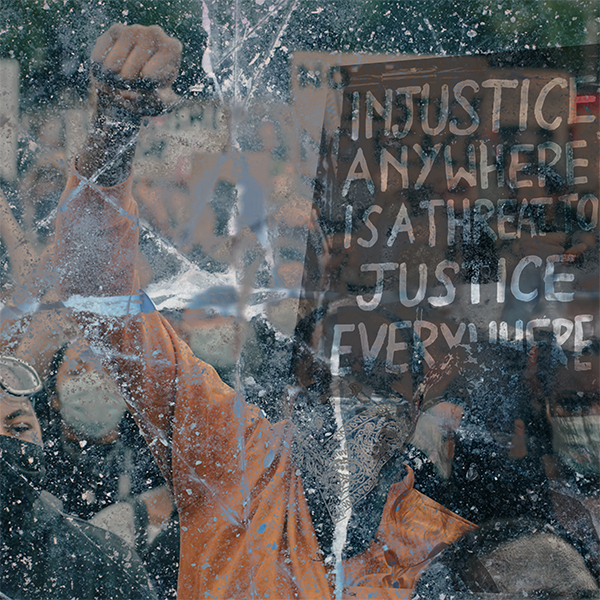

Like many others, on January 6, 2021, I discovered that the sentiments expressed in that out-of-the-way Indiana yard were more widespread than I’d understood. We also learned the name for the ideology behind these attitudes: Christian Nationalism.

In addition to the many signs and symbols blending Christianity and nationalism that were displayed during the January 6 protest and the ensuing violence, research cited in a report from the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty (BJC) found that those most supportive of the insurrection hold beliefs associated with Christian Nationalism. But, as many already understood long before January 6, Christian Nationalism is more widespread than the occasional, if spectacular, protest, and its expressions are not always so obvious.

Before suggesting how our churches might apply the gospel fruitfully to Christian Nationalism, we need to understand more precisely the contours of it. In their book, Taking America Back for God, sociologists Andrew L. Whitehead and Samuel L. Perry define Christian Nationalism as,

a cultural framework that blurs the distinctions between Christian identity and American identity, viewing the two as closely related and seeking to enhance and preserve their union. It is undergirded by identification with a conservative political orientation (though not necessarily a political party), Bible belief, premillennial visions of moral decay, and divine sanction for conquest. Finally, its conception of morality centers exclusively on fidelity to religion and fidelity to the nation.

In the BJC report, Whitehead and Perry note that Christian nationalists believe “that true Americans are white, culturally conservative, natural-born citizens.” Importantly, Christian Nationalism is not Christianity as historically understood, though it “relies on Christian imagery and language.”

Christian Nationalism is not Christianity as historically understood, though it “relies on Christian imagery and language.” (Andrew L. Whitehead and Samuel L. Perry) Share on XThis is not a new phenomenon. In the same report, Anthea Butler traces its origins to the nation’s founding as she points out that slavery enabled Christian Nationalism “by asserting that enslaved Africans were not human—in part by using scriptural justifications to support it.” Butler traces the persistence of this ideology through the “Lost Cause” narrative after the Civil War, the reestablishment of the KKK, opposition to the Civil Rights Movement, and various expressions of American exceptionalism. While the ideology can be embraced by people of color, it cannot be separated from a legacy of racism and white supremacy.

In her book, White Evangelical Racism, Butler writes about a well-known sermon delivered by Tom Skinner, “the son of a Black preacher”—at the InterVarsity Christian Fellowship Urbana conference in 1970. “To a great extent,” Skinner said, “the evangelical church in America supported the status quo. It supported slavery; it supported segregation; it preached against any attempt of the black man to stand on his own two feet.” The overlap between Skinner’s assessment of white Christianity and that of Christian Nationalism is significant and the ways each props up the racial status quo shouldn’t be missed.

Despite its history, Christian Nationalism has seemed reinvigorated in recent years, as the Capitol insurrection exemplifies. In research that parallels that of Whitehead and Perry, sociologists Michael Emerson and Glen Bracey have shown that a majority of those who identify as “white practicing Christians” have more in common with what the researchers label “the religion of whiteness” than they do with historic Christianity.

Whitehead and Perry have found three defining characteristics common among Christian nationalists. First, is the pursuit of power. For adherents of Christian Nationalism, the ends justify the means. The second is enforcement of boundaries. Christian nationalists, “particularly if they are white, remain committed to the belief that real Americans—or at least ‘the good kind’ of Americans—are native-born, white Christians.” Finally, Christian Nationalism seeks to maintain order in the public sphere by regulating private worlds such as gender roles and sexual norms.

Christian nationalists, “particularly if they are white, remain committed to the belief that real Americans—or at least ‘the good kind’ of Americans—are native-born, white Christians.” (Andrew L. Whitehead and Samuel L. Perry) Share on XAs we think about how the gospel can be applied to Christian Nationalism, we need to recognize that there is a range of commitments to the ideology. Whitehead and Perry identify four different postures along the spectrum. On the one side are the resisters and rejecters who see the ideology as a threat. On the other side are the accommodators and ambassadors. The ambassadors are fully committed, believing, for example, that the “First Amendment was intended solely to keep the state out of the church’s business, not to keep religion from influencing politics.” Accommodators, on the other hand, lean toward nationalism but remain undecided on some of its key beliefs. This is the group that will generally be more open to moving toward a fuller expression of the gospel and away from the disordering characteristics of nationalism.

Understanding the syncretistic lineage of racism, nationalism, and Christianity that expresses itself today as Christian Nationalism can help us reckon seriously with this destructive ideology, including seeing where it manifests in our own congregations and communities. Watching for the commitments to power, boundaries, and control invites us to consider where our commitments to the gospel have not been fully formed. And recognizing the nuances among those who’ve been allured by Christian Nationalism can provide a hopeful way to apply the gospel in varied and unique situations.

Watching for the (White Nationalism) commitments to power, boundaries, and control invites us to consider where our commitments to the gospel have not been fully formed. Share on XIn part two—”Christian Nationalism: What Dismantles It“—I’ll suggest a few ways the gospel can undermine the unrighteous tendencies of Christian Nationalism.