How Our Ignorance Slows Racial Justice and What We Can Do About It

I didn’t always give much attention to racial justice. Much has changed, but it has been a journey.

While I was born in the racially divided South, I grew up as a White kid in the Midwest in a predominantly White middle-class neighborhood. Through athletics, I befriended some of the only Black kids at my high school. Our city was ninety percent White. During my junior year, I was the only White face among our tight-knit group of varsity sprinters.

I went on to seminary in the late 1990s at Oral Roberts University in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a university that was, and still remains, one of the more racially diverse Christian universities in the country. I grew up decades after the struggle for desegregation, and I knew Black people in high school, college, and seminary, but I did not know their stories. I remember the L.A. Riots of 1992, but I didn’t know the depth of the struggles of people of color in a personal way. In essence—I didn’t know what I didn’t know. I lived in Tulsa for three years and yet never heard anything about Black Wall Street or the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

I was ignorant of my ignorance.

In 1999 my young family moved to Americus, Georgia, where I served a nondenominational church as a youth pastor. Our rural town had Black neighborhoods and White neighborhoods, White cemeteries and Black cemeteries, and sadly, like many American towns, White churches and Black churches. I went on to become the pastor of our church. I began to get to know some of the Black ministers in our town. I began to know some of the few Black members of our predominantly White church. I listened to their stories of oppression, violence, and racial hate.

I learned about Clarence Jordan and Koinonia Farm where Black farmers and White farmers worked the land together. Koinonia Farm, just outside of Americus, experienced violence from White supremacists in the 1950s and persevered through a commitment to live out the gospel of Jesus through prayer and nonviolent resistance.

I began a journey of discovery of the suffering and struggle for racial justice. Yet as a White pastor in a predominantly Black town, I did little in my church to advocate for racial reconciliation because I had subscribed to the homogeneous unit principle, a missiological theory that trapped my theological imagination in a White middle-class world.

The Homogeneous Unit Principle

Developed by American missiologist Donald McGavran at Fuller Theological Seminary, the homogeneous unit principle is the concept that people convert to Christianity at a higher rate, and thus churches experience more numerical growth, when they do not have to cross socio-economic, racial, or cultural lines. In the preface to the third edition of McGavran’s Understanding Church Growth, Peter Wagner writes, “‘People like to become Christians without crossing racial, linguistic, or class barriers,’ said McGavran. Conversion, he argued, should occur within a minimum of social dislocation. . . . The homogeneous unit principle is an attempt to respect the dignity of individuals and allow their decisions for Christ to be religious rather than social decisions.”[1]

In the 1980s and 1990s pastors who trained at Fuller took McGavran’s ideas to the suburbs of metropolitan American cities and experienced church growth in monoethnic churches. While McGavran may not have intended to infuse missional zeal with racist tendencies, his widely accepted theory has provided the framework for predominantly White churches to grow without much contact with brothers and sisters in Christ of another race. White isolation has prevented many White Christians from coming up close to the struggle of Black Christians.

White isolation has prevented many White Christians from coming up close to the struggle of Black Christians. Share on XI learned this theory in seminary from a professor who was a Fuller graduate. It strips the gospel of all its public and social implications. Accepting Jesus into one’s life is easier than accepting a person of a different race or culture into one’s life. While removing cultural and racial barriers from the process of making disciples does make the work of building the local church easier, it doesn’t look like the kingdom work we see in the New Testament. From the birth of the church on the day of Pentecost, the renewed people of God who received the Spirit of God were a multiethnic people.

While removing cultural and racial barriers from the process of making disciples does make the work of building the local church easier, it doesn’t look like the kingdom work we see in the New Testament. Share on XAs Rich Villodas writes, “The cross of Christ isn’t just a bridge that gets us to God; it’s a sledgehammer that breaks down the walls that separate us.”[2] Racial justice will never be a priority while the homogeneous unit principle drives the mission of the church. We need a renewed emphasis on the first-century gospel, the King Jesus gospel, in order to motivate God’s people in general, and White Christians in particular, to participate in racial justice.

The King Jesus Gospel

Peter stood up on the Day of Pentecost and preached the gospel. He punctuated his gospel message by saying, “God has made him both Lord and Messiah, this Jesus whom you crucified” (Acts 2:36). We don’t make Jesus Lord by asking him into our hearts. God made Jesus Lord when he raised him from the dead. The issue is not so much what we think about Jesus, but whether or not we are going to submit to him as Lord and King. In doing so we will enter his kingdom.

We don’t make Jesus Lord by asking him into our hearts. God made Jesus Lord when he raised him from the dead. The issue is not so much what we think about Jesus, but whether or not we are going to submit to him as Lord and King. Share on XThe gospel as rooted in the story of Israel is the rise of Jesus as King over the whole world, both the Jewish world and the Gentile world, fulfilling the promise given to Abraham that all the families of the earth would be blessed through Abraham (Genesis 12:3). The secret God revealed in Jesus is that Abraham’s family would be multiethnic, as the blessing of Abraham would come upon the Gentiles (Galatians 3:14). The Gentiles, by faith in Jesus as Messiah, would be included in the family of God.

The results of the proclamation of the King Jesus gospel includes the forgiveness of sins, the entrance into God’s kingdom, and the formation of a new humanity—a new family made up of Jews and Gentiles. Jesus doesn’t save us simply to take us to heaven upon death. Jesus saves us so that we can become new creations living as the anticipation of God’s new creation within a new multiethnic, transnational family. Derwin Gray adds, “Jesus now set Jews and Gentiles free from slavery to sin and death. He saved them from slavery and for inclusion into his family.”[3]

Jesus doesn't save us simply to take us to heaven upon death. Jesus saves us so that we can become new creations living as the anticipation of God’s new creation within a new multiethnic, transnational family. Share on XLiving as a multiethnic people in community who cast off the homogeneous unit principle, Christians can grow in their care and concern for racial justice by doing at least these four things:

Listen to the Stories Told by People of a Different Race

If we are going to get to know someone we need to listen to their story. The hearts and imaginations of White Christians will expand when they take the time to listen to the stories of Black, Asian, Latino, and Indigenous Christians. If I want to understand the suffering of people of color, I need to ask to hear their stories. Black Christians have learned to live in a White world, and because of that, many White Christians don’t think to ask questions and so are still ignorant of their ignorance.

Bear the Burdens of the Racially Oppressed

From the beginning, the Christian community has been one to look out for the marginalized and oppressed, compassionately caring for those who are hurting. To bear the burdens of another is to fulfill the law Jesus gave us (Galatians 6:2). For far too long I did not feel I had any obligation to participate in racial reconciliation because it wasn’t “my issue.” I hadn’t experienced racial discrimination, so why should I be bothered by those who do? Such immature reasoning is not in line with the truth of the gospel. The truth is God has a large multiethnic family, and I am a part of it. We are the multicolored body of Christ and when one of us are hurting, we all hurt.

Pray Prayers of Lament and Cry Out for Justice

To lament is to enter into the suffering of others and ask God for justice. The justice we seek is not vengeance or punitive retaliation. When we pray for justice we are petitioning God to make things right. We pray in order to attend ourselves to the presence of God and allow the Holy Spirit to point us to Jesus. It’s easy to give into anger and rage over injustice and impulsively do something. For Christians, the formation that occurs in prayer precedes the work for justice we do in the world.

Advocate for Racial Justice

Once we have prayed, then we are ready to act. Dr. King stated with unmistakable clarity that “Justice too long delayed is justice denied.”[4] Patience is the summation of the Christian wisdom, no doubt. Patience allows us to walk the path of nonviolent resistance in the ways of Jesus, but patience doesn’t imply doing nothing.

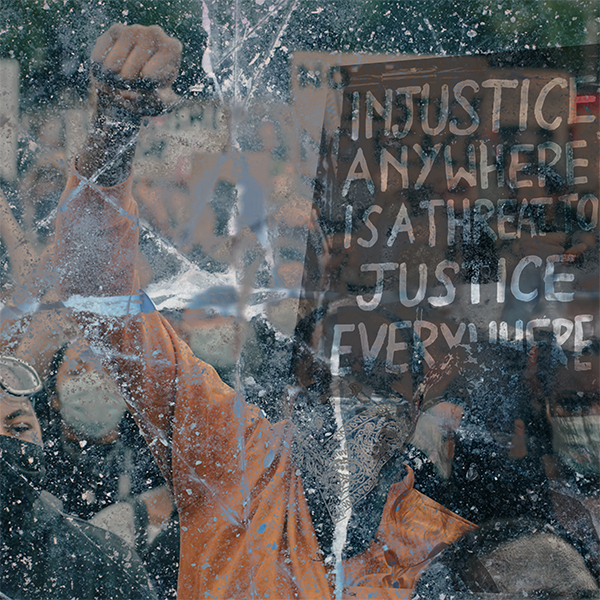

Advocacy for racial justice will look different for different Christians. For some, advocacy looks like volunteering to tutor in under-resourced neighborhoods. Others will advocate for justice in the public square by shining a light on injustice. Some will advocate for justice through peaceful protests. And others will advocate for justice by political means. We maintain Christian unity by allowing people to advocate in the way their consciences direct them.

Patience allows us to walk the path of nonviolent resistance in the ways of Jesus, but patience doesn't imply doing nothing. Share on XWe may be ignorant in our ignorance, but as followers of King Jesus we cannot remain that way.

[1] Donald McGavran, Understanding Church Growth , Third Edition, ed. by C. Peter Wagner (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1990), x.

[2] Rich Villodas, The Deeply Formed Life (Colorado Springs, CO: Waterbrook, 2020) 46.

[3] Derwin Gray, How to Heal our Racial Divide (Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale, 2022), 82.

[4] Martin Luther King, Jr., “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”