Awakening to Creation is Key for Flourishing Churches in Post-Christendom

In the coming years, creation will be a centering theme for flourishing churches. As society becomes increasingly post-Christian, our growing consciousness of our interconnectedness with creation and our responsibility toward it will be a key and integrating characteristic for discipleship.

Flourishing churches will seek to live, garden, work, and eat thoughtfully in relation to the creation, aware of their interdependence with all of creation. To put it in musical terms, creation will be the “key” that we play in, even as Jesus is our tune.

If this sounds like a bold claim, let me put it in historical context. As Western culture journeys more deeply into our emerging post-Christian reality, the church is being located at the margins of society. Our location at the margins puts us in a similar social location to the early church, which had little access to power. Yet as we embrace our new social location, two staggering differences distinguish our experience from that of the early church:

- First, today we are faced with the history, behaviors, and false identities entailed in the church’s complicity in the harmful aspects of Western history and culture.

- Second, we are a part of the Anthropocene, in which humanity is a primary agent in unalterably shaping planet earth. The Anthropocene is an era when humanity is the prevailing force in all of creation. Today, there is no place on the earth where human influence is not felt. Yet human impact is not only felt, but produces irreversible damage, notably global warming and species extinction.

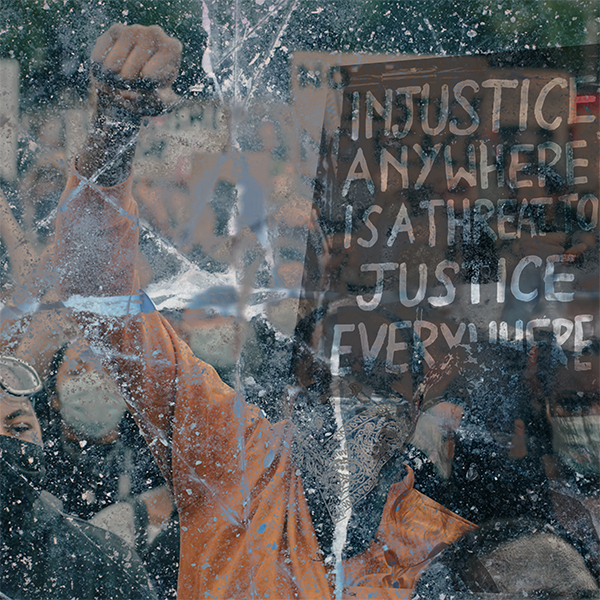

In post-Christian societies, as we seek to live faithfully into the biblical story, and as we vacate centers of power, flourishing churches will find their identity with the poor and with the creation.

“His Eye Is On The Sucker”

This is illustrated in the experience of my friend, Leah Kostamo. Leah is a co-founder of A Rocha Canada, a Christian organization dedicated to conservation and research, education, and sustainable agriculture.

Leah was invited to present at the University of Ottawa, Canada. She spoke on the topic, “The Future of Religion in Canada: Utopia and Dystopia?”1 Margaret Atwood, who is arguably Canada’s most renowned novelist, also presented. In her presentation, Kostamo told the story of an intern at an A Rocha farm. The intern rose one morning with a conviction that God would surprise her that day. (When Kostamo said this, “You could feel the skepticism rise from the crowd,” an onlooker commented.)

Later that day on a routine fish count in the Campbell River, the intern gathered a fish that was identified as an endangered species, the Salish sucker. This species hadn’t been identified in the vicinity for years! Leah reflected on God’s role in this story: “His eye is on the sucker,” she said, reappropriating the words of an old hymn.

This phrase was repeated throughout the remainder of the event by both Atwood and Kostamo: “His eye is on the sucker.” The Canadian university humanities context is often deeply hostile toward Christianity. Yet even there, Leah’s witness was not only authentic, but it was also compelling.

When Leah returned from Ottawa and shared her story, our common friendship circles were buzzing with excitement. Through Leah’s example, God showed us once again that living deeply into Christ’s way and speaking authentically from that place is truly beautiful, and is often warmly received, even as it also challenges and unsettles.

Stories like this make me curious: As we journey more deeply into post-Christendom, creation can be a centering reality connecting many aspects of Christian discipleship within flourishing churches. Becoming conscious of our connection with creation can reawaken the vitality and witness of the church.

Human Kinship with the Creation

This vision for the church is supported by the central role that creation plays in Scripture. Think of human responsibility toward creation, seen for example, in the requirements surrounding meat consumption found in Genesis 9:3-6. Humanity may kill living creatures for food, but only so long as the life of living creatures is revered: “Only, you shall not eat flesh with its life, that is, its blood” (Gen 9:4). The prohibition against consuming blood is ancient code for reverencing what has been made, of honoring the living creatures with whom God has covenanted.

Yet humanity is not obligated to the creation as other than the creation but as a part of the creation. We are made from the dust of the earth: the adam is taken from the adama (soil; Gen 2:7). Humanity comes from soil, returns to soil, and is ever related to soil. Such a mutuality of being is what sociologists refer to as “kinship:” humankind is kin with the non-human creation.

While at first glance the idea of human kinship with creation may sound overly romanticized, when we recognize with cultural anthropologists that kinship is a mutuality of being, an entangling of fortunes, we can see that kinship is exactly how Scripture presents human relationship with the nonhuman creation.

Creation Care?

Some thinkers have reflected that this human interdependence with the creation should give us pause to wonder whether “creation care” is always the most helpful phrase. The phrase “creation care” may give the impression that this relationship is a one-way street. We can overlook what ancient Israelite farmers could never overlook: that we are relentlessly interconnected with the earth. To be sure, humankind is called to care for the creation, and yet our care will need to be aligned with the reality that we ourselves are nourished by creation at every point. Creation is our mother, North American First Nations tradition says. As Dr. Ray Aldred, a Cree elder and theologian in Vancouver, puts it: “We don’t care for the creation; the creation cares for us!”2

Reintegrating Discipleship

Almost every aspect of Christian discipleship connects with creation, expressing, in one way or another, humanity’s bond with other creatures. Creation and environmental issues are intimately related to the social, emotional, spiritual, economic, and physical dimensions of our lives. Let me enumerate some ways in which creation can be a centering reality for many aspects of discipleship.

For one, Kostamo’s experience has shown us how intimacy with the creation opens a door for genuine speech about Jesus.

Second, consider the theme of hope. Many young people lack hope for the future. If violence against humanity colors how Gen-Z understands the past, violence against the creation colors how they anticipate the future. Perhaps surprisingly, in her talk, Kostamo repeatedly returned to the theme of hope: The “Christian message is one of hope,” she said. Kostamo admitted that some will think that hope is “Pollyannaish.” And yet the resurrection of Christ grounds Christian hope. And there in Ottawa it was the Christian community of A Rocha, with its thick and tangible connection with the creation, that gave Christian hope plausibility and form.

Third, in an era when faith is vulnerable and must be nourished with care, faith in God can be strengthened as we become conscious of our connection with the creation, our responsibility to care for creation, and the privilege of being cared for by creation. We see this dynamic in the biblical character of Job, for example. In the midst of Job’s darkest dark, he is reoriented in relation to God by considering the grandeur and intimate wonder of the creation (Job 38–41).

We see a connection between faith and creation also in the creation psalms, where the creation leads the psalmist to praise God (Ps 104; 148). A note for worship leaders: We shouldn’t settle for merely repeating the creation Psalms verbatim, since they arose from the ecosystem of Syria-Palestine. But we can encounter God afresh when we inquire into the unique ways our ecosystem reveals God. Can you write songs that name the trees and mountains in your vicinity? In this way we follow the psalmist’s example.

Fourth, creation relates to Scripture. If Wendell Berry is right to say that the Bible is an “outdoor book”3 — and I think that he is — then we will connect with the Bible more deeply as we become more aware of our connection with the creation.

Fifth, I have noticed that those who seek to learn about the creation tend to naturally adopt a learning posture toward First Peoples, as the ancient custodians of the land. First Nations’ wisdom for “walking in a good way on the land” begins with the conviction that they don’t own the land, but they belong to the land. This resonates with what we observed in Genesis 2:7 — we are taken from the adamah.

Sixth, and most importantly, we can meet Christ in the creation, for as Irenaeus put it, the incarnation is a “recapitulation of creation.” Wirzba summarizes Irenaeus, stating that Jesus entered “fully into the life of humanity and all creation so as to heal and transform it from within.”4

In sum, in my view the church can nourish a deep and vital faith by recovering our relationship with the land, the creation. This is especially so given the violence of colonialism, which distorts human relationship with the land. This includes the undisclosed ways in which warfare of displacement, slave holding, creation destruction, racism, and genocide have shaped (and are shaping) our spiritual experiences and assumptions.

Creation in Incarnational Communities

How can we become more attentive to our kinship with the non-human creation? So often, when we come to a fresh recognition of environmental degradation, we often respond with browbeating: “We’ve done so badly—let’s do better from now on!” And yet I find in my own life that the energy behind this kind of pep-talk-to-self quickly fades. Alternatively, forcing our way into the next creation care project-extravaganza, as promising as it may be, may recapitulate our sense of human mastery rather than forging the deeper transformation that is needed.

Instead, deep roots are formed through connection, over time. We need to nurture our awareness of our mutual interdependence with our fellow sixth-day creatures. Our kinship with other creatures — from trees to bacteria — is always there, but can we see it, can we seek integration in our lives?

Churches can connect with the creation in the way they live in their neighborhood. For example, by purchasing food from local farms as a group, we can be a part of sustaining healthy food systems. (A group in our church purchases from local farms.) We can partner in solidarity with indigenous groups as they take the lead in defending natural habitats. Our church building is used by First Nations groups for land defense meetings. I receive an education by simply sitting at the back in these meetings and keeping quiet.

And churches can partner with NGOs such as A Rocha in their education and sustainability efforts. One church took responsibility for building a set of stairs in a high traffic part of the local forest to prevent erosion.

Next is artisan work: bread for the Eucharist lovingly baked within the community (with hand-ground flour?); a table for communal meals created from a tree that used to stand in the church carpark. And then there is intentional learning. For example, our church went on a learning tour of our local watershed.

Though we need not and cannot return to preindustrial pastoralism, we can learn to live “as if this is the land that feeds you, as if these are the streams from which you drink, that builds your body and fill your spirit,”5 as Robin Wall Kimmerer puts it. The task of the church is one of remembering, of awakening to our connection with creation, and of “living in a good way.” In this way, the church can be a place of healing, where practices for remembering our connection with the creation nourish humility, wonder, and joy, in the presence of Jesus.

*Editorial Note: This piece is an edited excerpt from Mark R. Glanville’s Improvising Church: Scripture as the Source of Harmony, Rhythm, and Soul, which was released last month as a part of the Missio Alliance & IVP Book Series. ~CK

Footnotes:

1 This story is told in “Leah Kostamo and Margaret Atwood in Ottawa,” Kara Mandryk and Keith Hyde. See https://arocha.ca/his-eye-is-on-the-sucker/.

2 Ray Aldred, lecture delivered at Regent College, 2021.

3 Wendell Berry, Sex, Economy, Freedom & Community (New York: Pantheon, 1993), 103.

4 Wirzba discusses Irenaeus’s concept of the recapitulation of creation in From Nature to Creation: A Christian Vision for Understanding and Loving Our World (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2015), 23.

5 Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass, 214.