Christianity’s Growing Cultural Identity Crisis

On Inculturation and the Infinite Translatability of the Gospel

We are living in “VUCA” times –Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous.1This term was coined by the US Army to describe the historical time period following the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War. Covid, Gaza, ethnic strife, climate catastrophe, anti-immigrant rhetoric, political division, and so much more. It is perhaps not surprising that such volatility has extended into the Christian religious sphere of the United States. White Christian nationalism has unabashedly overrun much of Evangelicalism, and it has led to a breaking point for millions of people, both young and old. It is estimated that one million young adults are leaving the church each year. The following note I received from a student is reflective of our VUCA times:

“As a Latino growing up as the son of an undocumented pastor, my experience was much different from those who surrounded me. I felt that I could not identify with my peers and I always felt out of place. My white peers accepted me in the way that I stood in right by being [part of their denomination], but I was not accepted because of my skin color, my race, or my father’s undocumented status. I wanted to believe in what my family and church taught me as truth but I slowly drifted away from my beliefs as a result of the testimony I received from the Anglo church and their members. Even to this day those same Protestants refer to us as ‘wetbacks, beaners, and spics.’ I find myself conflicted with my identity.”

Such questions of cultural identity are now front and center for many Christian young adults as they are for my student. This is a natural consequence of the surge of white Christian nationalism since 2016. In essence, they are asking the following:

- What does my cultural heritage have to do with my faith in Jesus?

- Does God care about my Latinidad, or other marginalized ethnic identity, in the face of blatant racism in society and the church?

- Do I have to throw away my cultural identity in order to be a Christian?

- As a logical corollary, some ask, ‘Does God care about the injustices experienced by my ethnic community?’

What most people don’t realize is that such questions about the relationship between Christian faith and ethnic culture are as old as the Church itself. The Church has faced similar questions ever since the Gospel first extended beyond its original Jewish cultural context in the book of Acts, and every time the Gospel has crossed a new cultural frontier. For 2,000 years the Gospel has been crossing borders. Unlike every other major faith tradition, Christianity has never had a permanent geographic center. It is by nature, polycentric. We have forgotten this because European colonialism over the past 500 years made the strange and unprecedented claim that Christianity was to be equated with its own culture.

Notice how this contrasts with the testimony of the early church:

“Christians are indistinguishable from other men either by nationality, language or customs. They do not inhabit separate cities of their own, or speak a strange dialect, or follow some outlandish way of life. Their teaching is not based upon reveries inspired by the curiosity of men. Unlike some other people, they champion no purely human doctrine. With regard to dress, food and manner of life in general, they follow the customs of whatever city they happen to be living in, whether it is Greek or foreign.

And yet there is something extraordinary about their lives. They live in their own countries as though they were only passing through. They play their full role as citizens, but labor under all the disabilities of aliens. Any country can be their homeland, but for them their homeland, wherever it may be, is a foreign country” (Letter to Diognetus, circa 130 AD to 3rd Century).

For 2,000 years the Gospel has been crossing borders. Unlike every other major faith tradition, Christianity has never had a permanent geographic center. It is by nature, polycentric. (1/2) Share on X

We have forgotten this because European colonialism over the past 500 years made the strange and unprecedented claim that Christianity was to be equated with its own culture. (2/2) Share on X

As a polycentric faith, Christianity has exhibited one common pattern throughout its history: Christianity thrives in one geographic center for a time; eventually that center experiences a decline, and another rises to take its place.2Andrew Walls, The Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1996), 16-25. For more on the concept of polycentric Christianity, see: Allen Yeh, Polycentric Missiology: 21st-Century Mission from Everyone to Everywhere (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2016). In this manner, global Christianity was centered in the Near East, Asia, and Africa for 1,000 years before it became dominant in Europe. Christianity spread from the Roman Empire eastward to Turkey, India, Armenia, Georgia, Iran, Syria, Sri Lanka, Iraq, China. Christianity has had a near continuous 2,000 history in the Near East, Africa, and Asia, and Christianity first came to China at the same time as England. The theological origins of Western Christianity lie in North Africa with Tertullian, Cyprian, Origen, and Augustine. In light of this expansive history, the Protestant Reformation can be considered a relatively recent, though nonetheless important, Northern European cultural expression of Christianity.

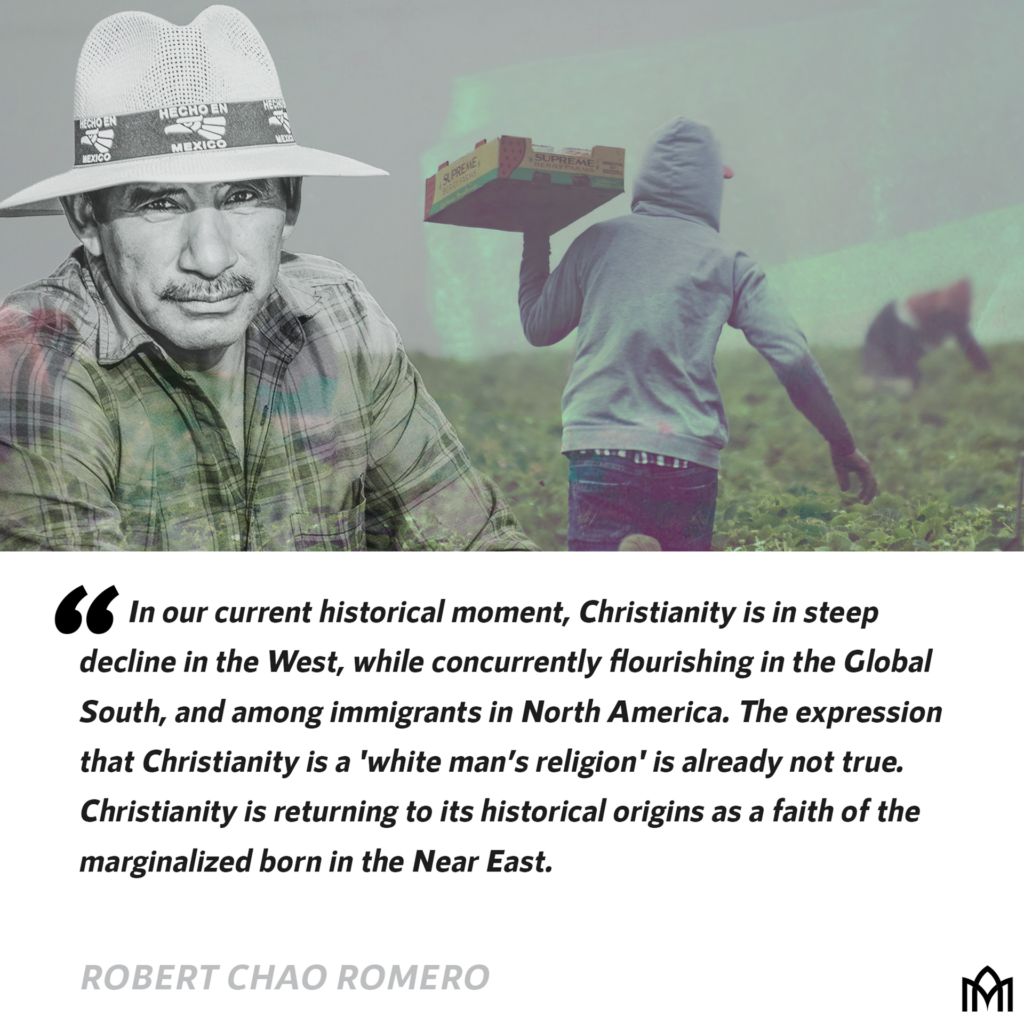

In our current historical moment, Christianity is in steep decline in the West, while concurrently flourishing in the Global South, and among immigrants in North America. The expression that Christianity is a “white man’s religion” is already not true. By 2050, moreover, it is estimated that the majority of Christians in the world will live in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, with four out of every ten Christians residing in sub-Saharan Africa. Christianity is returning to its historical origins as a faith of the marginalized born in the Near East. In the decades to come, Christian immigrants from Latin America, Africa, and Asia will redefine the US church in practice, polity, and theology.

According to Andrew Walls, this pattern of Christianity’s rise and fall in different geographic centers has occurred six times throughout world history and is a Christian distinctive. Walls writes, “Christianity is a generational process, an ongoing dialogue with culture…The full-grown humanity of Christ requires all the Christian generations, just as it embodies all the cultural variety that six continents can bring.”3Walls, The Missionary Movement, xvii, 22. Christianity is infinitely translatable and the Gospel is a “liberator of culture.”4Ibid., 3,22. Christ sanctifies us individually, and our cultures corporately, allowing our cultural treasures to shine more brightly as a sweet offering to our Savior for eternity (See Revelation 21:26). Each time the Gospel is received by a new people, in a new culture, the universal church grows in maturity and understanding. In the words of Filipino theologian José de Mesa, “God appears to us through the burning bush of our cultures.”

Over the past 2,000 years, every time the Gospel has crossed a cultural frontier, the question of cultural identity has by necessity always eventually arisen. This is because the good news of Jesus is passed on from one people group to another through the process of inculturation. Peter Phan defines inculturation thusly:

“Inculturation is a two-way process comprising (a) insertion of the Gospel into a particular culture and (b) introduction of the culture into the Gospel…The result of inculturation is the transformation of both the culture from within by the Gospel and the enrichment of the Gospel by the culture with new ways of understanding and living it. Hence, the end result of inculturation is something new, a tertium quid, going beyond the current culture and the previous ways of understanding and living the Gospel the previous ways of understanding and living the Gospel.”5Peter Phan, “Mission as Inculturation: Contextualizing God’s Message in Local Cultures,” in, ed. Kirsteen Kim, The Oxford Handbook of Mission Studies, 420-436; 423.

According to Walls, when Christ enters a new cultural group, he addresses their unique questions and concerns which flow from their own language, cultural context, and cultural categories. This he calls the “indigenizing principle.”6Walls, The Missionary Movement, 7-8; 28. Such questions and concerns might not even make sense in different contexts or historical times (e.g., Think about questions of the Internet to previous generations of Christians). The Gospel becomes re-expressed in new cultural forms and the process of Gospel incarnation leads to new discoveries about Christ which benefit the entire Body of Christ.7Ibid., 23, 27. The Body of Christ grows one step closer to maturity. The Body of Christ “grows an inch” (See Ephesians 4:13-16).

As a polycentric faith, Christianity has exhibited a common pattern throughout history: It thrives in one geographic center for a time; eventually that center experiences a decline, and another rises to take its place. (1/5) Share on X

In light of this expansive history, the Protestant Reformation can be considered a relatively recent, though nonetheless important, Northern European cultural expression of Christianity. (2/5) Share on X

In our current historical moment, Christianity is in steep decline in the West, while concurrently flourishing in the Global South, and among immigrants in North America. (3/5) Share on X

By 2050, moreover, it is estimated that the majority of Christians in the world will live in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, with four out of every ten Christians residing in sub-Saharan Africa. (4/5) Share on X

Christianity is returning to its historical origins as a faith of the marginalized born in the Near East. In the decades to come, Christian immigrants from Latin America, Africa, and Asia will redefine the US church. (5/5) Share on X

Inevitably, the process of Gospel inculturation, or contextualization, leads to the question: What is the relationship between my cultural background and the Gospel?

In the 2nd century, for example, Origen of Alexandria asked what was the relationship between ancient Greek culture and learning, and Christ? Did God require him to abandon his training and profession as a teacher of Greek philosophy? What about the centuries of Greek wisdom represented by Socrates, Plato, Aristotle and Homer? Should it all just be thrown out? In a similar fashion, many Latinas/os today are asking, “How does my Christian faith relate to my African or Indigenous heritage? Do I have to assimilate into whiteness in order to be a Christian, or do I have to throw away Christianity in order to embrace my African or Indigenous roots?”

Origen’s determination was that Philosophy was to the Greeks what the Law was to the Jewish people — preparation for the full revelation of truth and salvation in Jesus Christ. Not that all of Greek philosophy was consonant with God’s full revelation in Christ, but that truth was present in Greek learning which pointed the way to ultimate salvation and redemption of the world, and all its peoples, in Christ.

Others like Irenaeus would do the hard work of sifting what aspects of Greek philosophy and worldview — specifically Gnosticism — were incompatible with Scripture and the teachings of Christ which had been passed down through the Apostles.8See Irenaeus, Against Heresies. It seems there were some in the early church who, without discernment, sought to fuse Christianity and Gnosticism uncritically, going so far as to claim that the God of the Old Testament was a lesser god than the God of the New Testament, and that Christ did not truly take on human flesh and blood. You might call this cultural retrieval without discernment. This occurs today as well.

Irenaeus, Origen, and Augustine all spoke about the refashioning of human cultures for the glory of God. They posed the question: Where did the Israelites get the gold and cloth and precious materials to construct the Tabernacle in the barren desert? Their answer: They received it from their Egyptians neighbors, as Exodus 3:21-22 describes:

“I will bring this people into such favor with the Egyptians that, when you go, you will not go empty-handed; each woman shall ask her neighbor and any woman living in the neighbor’s house for jewelry of silver and of gold and clothing, and you shall put them on your sons and on your daughters; so you shall plunder the Egyptians” (Exodus 3:21-22, NRSV).

Another parallel is the “gold from Parvaim” (2 Chronicles 3:6) which Solomon used to construct the temple.

The theological principle from these examples is that God redeems and refashions the cultural treasure and wealth of the different ethnic groups of the world for the glory of God.

Ultimately, this cultural treasure and wealth of the nations is of eternal value to God, as John describes near the end of his vision in Revelation:

“People will bring into it the glory [Greek “doxa,” meaning treasure or wealth] and the honor of the nations. But nothing unclean will enter it, nor anyone who practices abomination or falsehood, but only those who are written in the Lamb’s book of life (Revelation 21:26-27)

For those of us wrestling with understanding the relationship between our ethnic culture(s) and faith in Christ, this is good news. As my good friend, Orlando Crespo, writes in his deeply impactful book, Being Latino in Christ: “When we come to Christ we become more of who we are, not less.” And as proclaimed by celebrated African theologian, Kwame Bediako, after his conversion: “Christ has made me more African than I have ever been.”

///

I end with a short quiz of two questions, one ‘Fill in the Blank’ and one ‘True/False:’

-

- Christ makes you more ___________________ than you have ever been.

- 500 years of Colonialism and bad theology have made us forget this reality. True/False (Choose one)

If it is true that Christ redeems our ethnic cultures and makes us more of who we are, then how do we discern what aspects of our cultures represent the “glory and honor of the nations” (Revelation 21:26) and what aspects are “unclean” (Revelation 21:27) and will not make it in to the New Jerusalem?

This question will be the topic of future parts in this ongoing series on enculturation and communal discernment.

///

Each time the Gospel is received by a new people, in a new culture, the universal church grows in maturity. In the words of Filipino theologian José de Mesa, 'God appears to us through the burning bush of our cultures.' Share on X