What Art Does: An Artmaker’s Wisdom on Life and Leadership

As a young artist I was frequently frustrated. I purchased the best canvases and paints I could afford, I honed my skills, but the end product still left me feeling flat.

Now I know why: that way of making art with fresh new supplies, while an undoubtedly valid way to make art, didn’t feel like anything else in my life.

In the work of making a life we’re rarely given a fresh canvas, rarely offered materials which cooperate. We may feel like the ‘canvas’ we’ve been handed to create this life has already been marked by someone else’s work. Or perhaps that we’re working desperately to make something beautiful of this life, but all we’ve been given is scraps. In leadership this can feel even more the case — we could create a great organization if only we were given a fresh ‘canvas’ instead of unruly people and broken systems.

It turns out that while we think creativity comes from unlimited possibilities, the truth is that creativity flourishes when we have limits. In his 2013 TED talk, entitled “Embrace the Shake,” artist Phil Hansen describes the creativity that became possible when he embraced the hand tremor that had begun to “ruin” his art. “We need to first be limited in order to become limitless,” he concludes. This truth opens up hopeful new possibilities not only for how we make art but also for how we live and lead, because in all these places, we have limitless limitations!

In my faith and ministry, I’m constantly experimenting, asking: “What is mine to control and what is mine to release to things outside of my control?” Over the years I’ve processed this in my art-making. And the surprising discovery has been that my best art has come from embracing my lack of control. I often say “the way is the way” (and named my website for it!) because I truly believe that how we do something cannot be disconnected from what we’re trying to do. It turns out that my concept is not all that different from the brilliant phrase from the late Catholic communication theorist, Marshall McLuhan:

///

In the work of making a life we’re rarely given a fresh canvas, rarely offered materials which cooperate. We may feel like the canvas we’ve been handed to create this life has already been marked by someone else’s work. (1/3) Share on X

We’re working desperately to make something beautiful of this life but all we’ve been given is scraps. In leadership this can feel even more the case — we could create a great organization if only we were given a fresh canvas. (2/3) Share on X

It turns out that while we think creativity comes from unlimited possibilities, the truth is that creativity flourishes when we have limits. (3/3) Share on X

When we’re following Jesus, the way we live becomes the way we communicate. They will know us not by how perfectly we’ve worded our doctrines or defended our positions, but by our love — the medium by which we do it all. To be mean about the Good News, to be divisive in how we shape a community, to let anxiety lead when we claim to trust God — all of these make our message void. To focus primarily on the product when we build a church does real damage to the human lives and relationships that make up that community, because people are always in process. The artist knows that the process cannot be divorced from the product. The way we work behind the scenes in leadership — our assumptions, anxieties, motivations, and ways of communicating — can’t help but shape the outcomes.

But it takes deep work to live and lead from the right places, to allow the way in us to be shaped by Jesus. If we really want the way of Jesus to actually become our way, we’ll need to release control. And as we slowly empty ourselves of all our meanness, divisiveness, and anxiety, slowly Jesus is able to make his way in us.

The same is true in art-making.

In addition to the particular image we’re making (eg. a portrait of a face), the way we make the strokes tells a story. The same face will look vastly different depending on the way it’s made. If the artist makes quick strokes with a paintbrush, it may create a sense of energy. If, on the other hand, the artist uses small, light pencil marks, the exact same face might give the viewer an impression of calm contemplation.

And so, although it’s uncomfortable, when making art, I purposefully limit my control to allow the finished artwork to tell the story of partnering with forces beyond my own. Why do I do this? Because paint will drip and ink will bleed. I can fight it or embrace it. All of human life is made in partnership with things we don’t understand or control, so why not allow art about this life to be made in a way that the very method of its making communicates?

This way of making art has helped me know how to live and follow and lead. And I’m thrilled that some examples of my art are printed along with my words in my latest book, Confessions of an Amateur Saint: The Christian Leader’s Journey from Self-Sufficiency to Reliance on God. I hope that knowing the story behind their making adds to the story of my book.

///

I’m constantly experimenting, asking: 'What is mine to control and to release to things outside of my control?' I’ve processed this in my art-making. The surprising discovery? My best art has come from embracing my lack of control. Share on X

Here are six pieces of wisdom I am internalizing from the artists who inspire me, and the art it has inspired within me so far:

- The Gravity of Paint

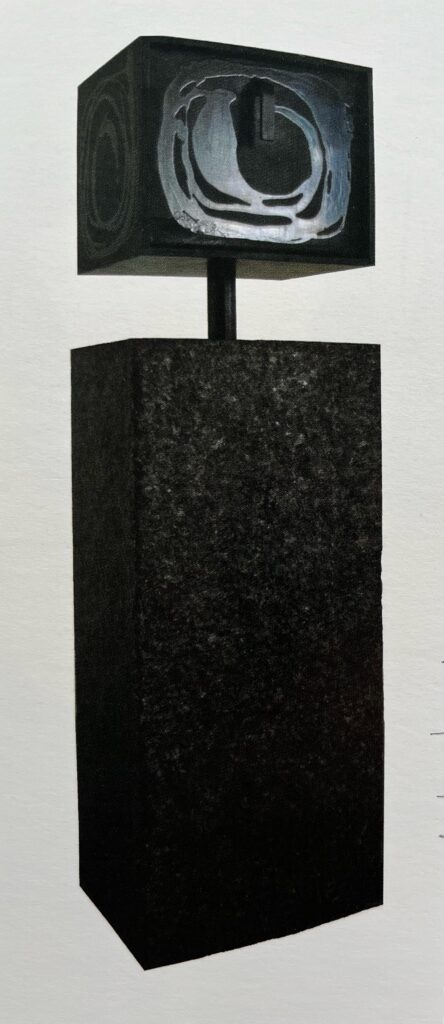

Usually I’m moved by the beauty of art, so I was surprised to be moved by a photo of this strange (almost ugly) piece — “Tabernacle,” made by William Schickel to house the Eucharist at Gethsemani Abbey. While the base of it is solid granite, Schickel decorated it with dripped enamel paint, describing how “the hard, solid form of the tabernacle and the spontaneous swirls and drips of paint” point to a “God who allows Himself to be contained — incarnate in the flesh and in the Eucharist — while at the same time He is the omnipresent Spirit who moves mysteriously through the world.” It took great control to carve granite into a perfect block and just a few seconds of play with gravity and paint to decorate it — life and faith can be like that.

“Tabernacle” by William Schickel (from Sacred Passion: The Art of William Schickel by Gregory Wolfe)

- The Flourish of a Brushstroke

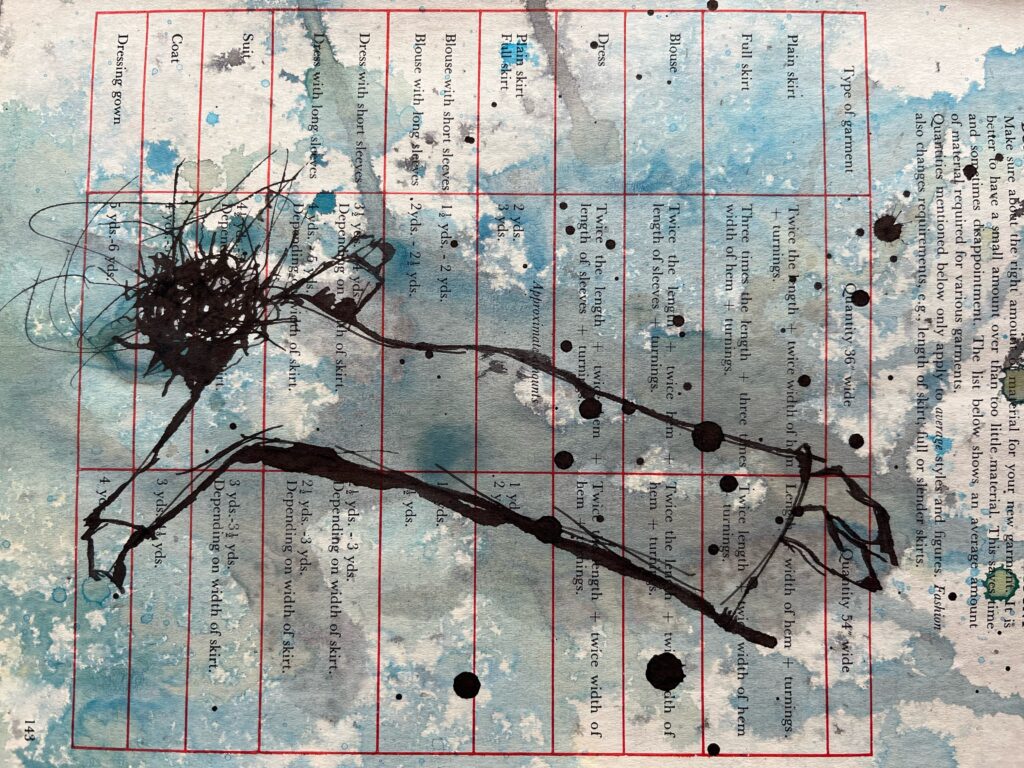

I was surprised to discover that Thomas Merton’s father was a professional artist and that Merton himself dabbled in art-making. Merton’s art, inspired by Japanese Calligraphy, is made with quick strokes, allowing for little over-thinking, trusting that the best shapes are made by letting the bristles of the brush move just as they were made to move. There’s no pencil sketch to plan first, and the ink is permanent, so there’s pressure to make it perfect. But the best strokes here are made with abandon.

“The monk is a bird who flies very fast” by Thomas Merton (from Angelic Mistakes: The Art of Thomas Merton by Roger Lipsey)

- The Unpredictability of a Homemade Pen

We might think of calligraphy as the art of making perfect hand-writing but some calligraphers use a cola pen, a hand-made dip pen made from soda cans, specifically because the thin aluminum moves in unpredictable ways, leaving very interesting marks and splotches.

See more here from calligrapher Ruth Rowland. Here is a second video where someone explains how to make and use your own handmade cola pen.

“Gethsemane” by Mandy Smith (ink with cola pen)

It takes deep work to lead from the right places, to allow the way in us to be shaped by Jesus. As we release control, emptying ourselves of all our meanness, divisiveness, and anxiety, slowly Jesus is able to make his way in us. Share on X

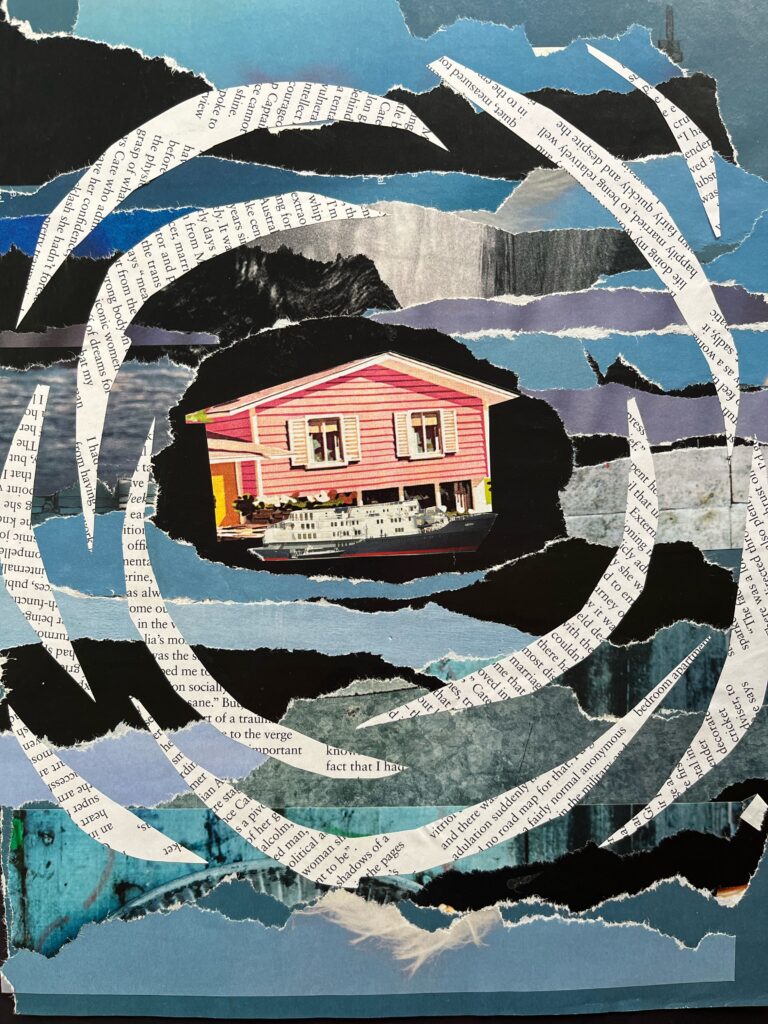

- The Unlikeliness of Scraps

I was first introduced to the wonders of collage through SoulCollage. At my first Soul Collage workshop, we quietly wandered among tables spread with magazine pages and chose a handful of images which resonated with us. For me it was an image of a pink house, a ship, and the ocean. I then sat with the images and arranged them, created a collage by pasting the images onto a card, and then discovering that my chosen images were actually all about my possessions being in a ship on the ocean during an international move. My whole life felt a bit adrift in this season, something I didn’t even realize I was feeling when I chose three seemingly random scraps of paper.

“Adrift” by Mandy Smith (collage)

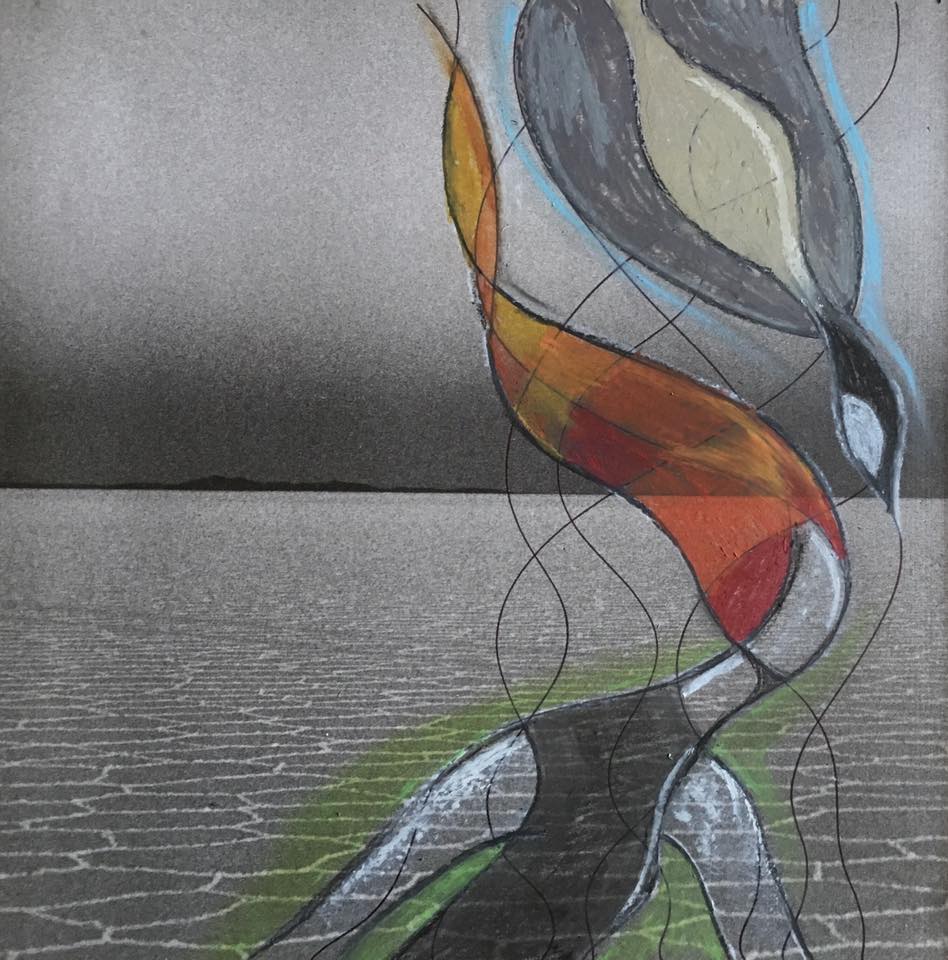

- The Possibilities of Scribbles

I came across this reflective art process by accident when scribbling one day. In the same way you can find an image in clouds or woodgrain, I saw a face between the lines and grabbed my colored oil pastels to fill it in. See this video for my process.

“Fly Like That” by Mandy Smith (pen and oil pastel on photo)

- The Jiggle of a Gel Plate

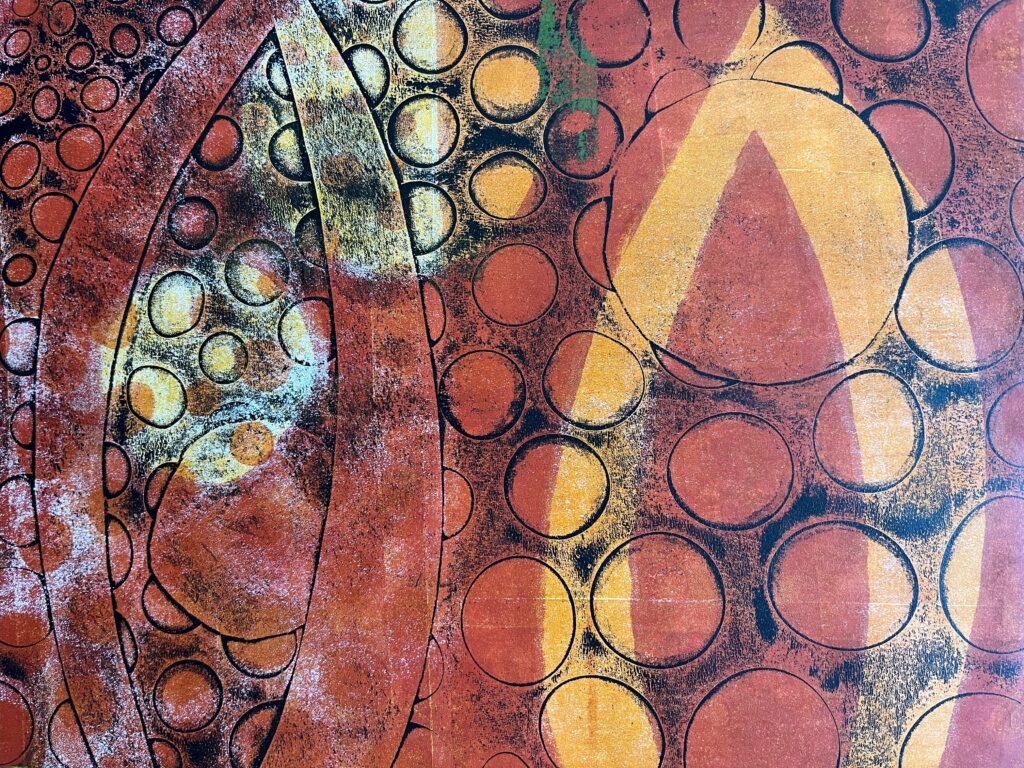

Workshops with Dianne Minnaar of Sanctus Sacred Images, in particular on creating sacred images, have taught me new ways to release control in art-making. One of the techniques she teaches is Gel Plate printing, which engages some human agency, but also releases control to see what happens when paint is applied to a jiggly rectangle of gel and a page is pressed upon it.

“Eye Pods” by Mandy Smith (Acrylic Gel Plate Print)

Although it’s uncomfortable, when making art, I purposefully limit my control to allow the finished artwork to tell the story of partnering with forces beyond my own. Why do I do this? Because paint will drip and ink will bleed. Share on X

New Ways of Making Things

All of this is partly about discovering new ways of making things — art is worth making for its own sake.

But after decades of being offered management models of church leadership, I’m hopeful to see how other ways of living also offer models for leadership. Management models which focus on controlling outcomes and creating a predictable product may be helpful when managing systems. But they’re not suited for work like ministry which requires capacity for mess and mystery. In such work, the artists among us (and in us) have deep experience. Artists love to talk about the process of making something because surprising and beautiful things happen in all that takes place between the start and the finish. Artists know that when they pay attention and engage faithfully with their tools and their medium, something will take shape which was partly their doing and partly the work of something beyond themselves – which sounds quite a lot like the work of partnering with God in mission. It’s freeing to know that whatever we’re called to do is not a soulless product for us to crank out robotically, but a watchful partnership, creating and being created.

///

All of human life is made in partnership with things we don’t understand or control, so why not allow art about this life to be made in a way that the very method of its making communicates? Share on X