How These Hero Children Revolutionized What it Means to “Advocate”

On a recent trip to Guatemala, I had a chance to glance the marvelous, the mundane, and the miraculous.

An Advocate of Voice

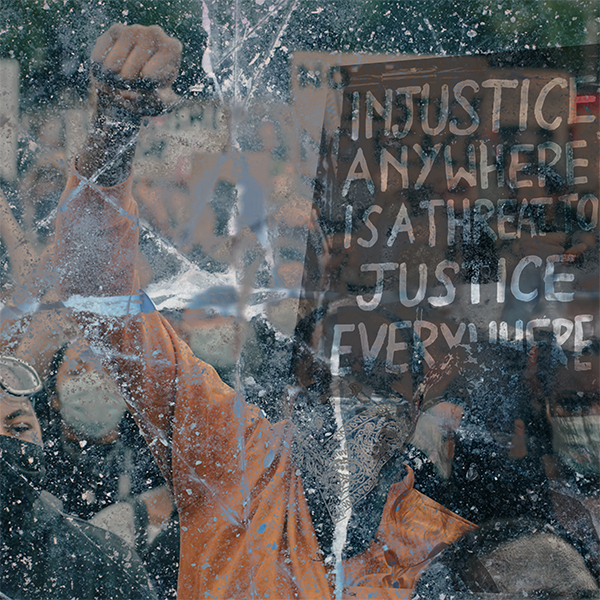

The marvelous moment—was beautiful and beyond what my heart could contain. For the past few years, I’ve been an advocate of voice. Voice for people on the margins, voice in all its forms, and particularly voice for ethnic minorities in the US. I traveled down to Guatemala to get a sense of the work there—my organization, IJM’s particular casework is on Child Sexual Assault. Recent war violence, a society in the healing process, and people intimately touched by the violence has, as one of its fruits, an invisible plague of sexual assault on children—by friends, fathers, grandfathers, uncles, and neighbors—that is consuming the moral fiber of the country.

Originally, we thought we would establish an IJM office, to address trafficking. But the rates of CSA were staggering, and we realized that this was the time and place for that.

Children are asked to testify, before a judge, a prosecutor, a defense lawyer. They are asked to testify, in a case where people usually don’t bring this kind of crime to court, to testify in a situation where it is highly likely that nothing will happen, to testify against an adult who committed acts that they feel ashamed or embarrassed about or confused. These children have to speak the unspeakable, the incomprehensible, before a judge.

These children have to speak the unspeakable, the incomprehensible, before a judge. Share on XThe Hero Pin

And for this, the IJM team gave them a pin. A hero pin. I was able to attend a pinning ceremony—an event much more fun that the name implies. It’s a pizza party, with a clown, and coloring, and a crafts table. It would feel like any other fun, ordinary kids party. But in the middle, after the clown got everyone to get up and dance foolishly, each social worker calls up each client, and gives them a hero pin. And they say a few words.

I saw three kids, in the same school uniform go up. Three clients, from the same family. I saw a woman, someone I thought was a mom, hand over her infant when her name was called, and go up to receive her pin. I later saw her coloring in her “hero” coloring page as eagerly as the 5 year old next to her. I saw girls, and I saw boys, one by one go up, younger than should be possible and receive their pin. And I wept through it all.

It was the commendation of one social worker, to her client, that hit me the most. “You are a voice,” she said. “A voice for all the others.” And my scanty, anemic definition of “voice” (and of “hero”) rolled over and died. Till then, “Voice” had meant speaking up, yelling if needed, when others stepped on my community, my gender. “Voice” was the rallying cry to get others to speak, make a ruckus, turn anger into action.

Here, in a conference room on a side street in Zona 1, in Guatemala, amidst smells of greasy cheese, and spilled soda, I saw a five year old embodiment of voice. Voice, is a child, speaking against a perpetrator, in front of other adults, of a crime that was committed against them. Voice is speaking, even when only 5% of people who commit sexual crimes against children ever have to go to jail for the crime. Voice is speaking, in front of a judge, who has thrown out these types of cases 7 times before. But the children don’t know this, they speak.

Heroes Without Capes

“Hero” is not a person in a cape. “Hero” is not a pastor who leads a big church, and publishes a lot of books. “Hero” is a child, five years old, maybe six, who speaks about a private and terrible crime, who speaks, even though the social cost to him or her is probably bigger than the social cost to the person on trial, being accused of the crime. “Hero” is a person who speaks, even when it’s hard, not likely to make a difference, but they speak for themselves, and as a result, unknowingly for others.

The ability to recover from the horrific, is truly miraculous. I passed it, as I entered the office. One of the office workers is a former client.

We visit in the home, a final visit to a client. A young boy, a victim of his uncle’s crimes. He is slow, developmentally challenged. And he finds our visit a quiet delight. He smiles, eyes on the table in front of him but doesn’t speak unprompted. Sitting around warm glasses of Coke, his social worker beckons him forward.

A hero speaks—not to make a difference—but for themselves & unknowingly for others. Share on XHe’s grown. Is he doing well in school? She asks about his favorite part of the program he graduated from. He silently goes back to his room—pulls aside a fabric draped in the doorway, into an unlit room, and pulls out his treasure box—a plastic pencil box. Inside are his two prized possession, a cell phone, and his hero pin. He holds the pin with pride, shows it to the director and says that the pizza party was his favorite part.

Mine too.