Can We Stop Making Statements on Sexual Ethics?

Dear Christian Leader,

Can we stop making statements and counter-statements on what constitutes the “real” or “biblical” or “orthodox” or “evangelical” position on sexual ethics?

I ask as a pastor who cares deeply about sexual ethics, who holds a high view of Scripture, and who even thinks that our understanding of sexuality is one of the places where we desperately need a deep, rich vision for Gospel flourishing and transformation.

And it’s not just me. Other on-the-ground pastors are saying this too. In response, big-name leaders behind the statements (and counter-statements) have suggested this amounts to not wanting to “go public” with our sexual ethic. We’ve got to stand publicly for the truth, they say. After all, how else would the watching world know what it means to apply the Gospel to their sexuality?

Measuring Our Witness

For these leaders, public pronouncements like the Nashville Statement amount to witness. Senior Fellow of the Council for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, Owen Strachan says, “The Nashville Statement … is Christian witness. There is no witness without it” (final emphasis mine). Thus, Strachan suggests that pastors who are cautious about these public pronouncements are choosing not to embrace a sexual ethic. Perhaps that is true in some instances, but I think it completely misses the point for others.

I submit that the hesitancy many pastors have is grounded in the conviction that public statements like these amount to an anemic ethic. Strachan insists that having a statement is part and parcel with what it means to have a sexual ethic. But we are asking you to stop making statements precisely because we’re trying to cultivate a robust sexual ethic within the concrete, diverse contexts and communities in which we serve.

We need to cultivate a robust sexual ethic within the diverse contexts we serve. Share on XPerhaps it is clarifying to name that the concern we are expressing about these statements is not primarily or exclusively theological. Truly, there are areas of agreement and disagreement about the nature of sexuality that God reveals in Christ and works in the Spirit. That is a conversation worth having. However, even if we assented theologically to each article of a statement, it seems like we have a fundamentally different understanding of what it means to be ethical.

We believe that sexual ethics are necessarily lived realities, worked out in daily practices in concrete communities among people to whom our words and actions are accountable. An ethic without flesh—without a body in which conversations are metabolized into particular actions—is not an ethic grounded in Jesus Christ. That is why an ethic that consists primarily in abstracted affirmations and denials is both unintelligible and disconcerting to us.

An ethic without flesh is not an ethic grounded in Jesus Christ. Share on XConcrete Communities & Contingent Realities

Lacking in these statements are the actual ways in which God’s gift of sexual flourishing in Christ might be enfleshed within concrete and contingent realities. The extent of ethical imagination generated in these statements is simply more affirming or denying. What does that even look like? Do I email these statements to the sisters and brothers I know wrestling with their sexuality, trusting that this time more theological information will suddenly illuminate a new way forward? Do I preach a fourteen-week sermon series, one for each article? I get that we can speak truth in love, but for goodness sake, how in the hell do we measure what counts or doesn’t count as “truth in love”?

In other words, we believe that what these statements lack is the ethical part. And the lack of grounded ethics mixed with the influence of these voices, further mixed with the power of the antagonism that characterizes the “Spirit of this Age” combine in way that causes more convolution than clarity. And it leads us to wonder, if these statements fail to cultivate a genuinely ethical imagination for sexual faithfulness, then what kind of work are they actually accomplishing?

To the non-Christian community: these statements reinforce the idea that Christians are more invested in condemning (or affirming) other’s [homo]sexual behavior than seeking healing within their own sexually-broken history. What does it say about our sexual ethic if our first instinct is to craft a statement that reinforces a standard we have traditionally believed but notoriously failed to put into practice? How many of those who “signed” the statements and counter statements are endorsing something they already believed anyway?

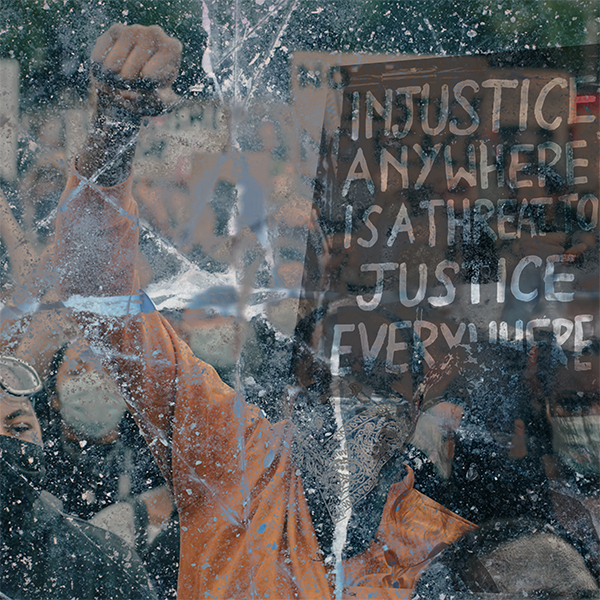

To the Christian community: by reinforcing the antagonistic structures that make us feel justified for being on the right side, these statements can push us out of the space where we are actively learning to spiritually discern and humbly surrender our sexuality unto transformation in Jesus Christ. We are trying to hold a tender, holy space beyond being on the right side (by the way, almost no one I know is confused about the position of our big-name leaders; many are confused, however, about how to navigate these issues in their actual lives). But these pronouncements come bursting in like an oblivious outsider, shouting answers and taking names. This disrupts current spaces where sexual ethics have already been metabolizing by offering an easy way out. It also forecloses future space through rhetorical force, narrowly defining the limits of ethical possibility around affirming and denying (that is the effect, anyway, even if that wasn’t the intention).

The #NashvilleStatement forecloses future space of conversation through rhetorical force. Share on XImagine if, instead, Christian leaders committed to lead by locally embodying sexual repentance (in every kind) and by holding forth practices in which everyone could catch a glimpse of what it means to surrender sexual brokenness and experience God’s “Yes” to human flourishing. Imagine if this local embodiment of sexual faithfulness became our first and primary impulse for witness.

In an age of antagonism, where posturing and pronouncements get substituted for substance, this is what we on-the-ground pastors are seeking.