Mental Illness: 7 Practices for Ministering Well—Even if You’re Not A Mental Health Professional

When I was 14 years old, my family was forced to reconcile reality with a long-held collective delusion. Mom had always been quirky, preoccupied, fragile. She was sometimes hard to understand, often fearful, usually alone. She was confused; she confused us. That was just her, we thought.

Until it wasn’t really her anymore—she got lost in her own delusions, in paranoid fear, buried by the voices in her head and the merciless kind of confusion that only untreated schizophrenia can produce. And Dad, who had been a pastor for 10 years, had to leave pastoral ministry.

For all our denial of reality—comforting ourselves with the mistaken belief that Mom would keep “snapping out of it”—we had no choice but to acknowledge her illness. Severe mental illness was part of our family and had been since the family was formed. And ultimately, recognizing the truth was the most important step in helping Mom get the treatment she needed.

Many church leaders live with their own delusions about mental illness. Since I began writing about my family’s story, encouraging churches to engage in our mission toward people living with mental illness, and speaking to churches on this topic, I have had many conversations with people in ministry who are—with wonderful and welcome intentions—wondering whether their churches should get involved in ministry to people with mental health challenges.

But this wondering is rooted in a delusion: if you want to minister to people, you don’t really have a choice. Churches are already neck-deep in this kind of ministry.

Let’s Face Reality

You probably realize folks come to the church with all sorts of needs and concerns. What you may not recognize is that this holds true for people who live with mental illness. Historically, when people seek help for mental illness, they go first to a member of the clergy. This is true for a variety of reasons, including a mental health care system that is notoriously difficult to access and relies on people with brain-based disorders to manage their own care through that system. Other reasons are inherent in the nature of faith communities: they offer spiritual experiences, promises of peace and joy, opportunities for community, and for communion with God. These elements of church life are understandably attractive to many people with mental illness. Churches have a special responsibility to recognize this and respond intentionally.

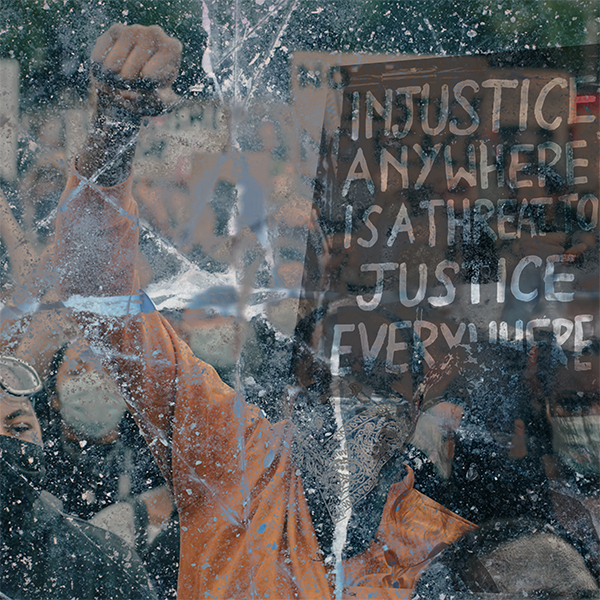

And when it comes to our mission as the body of Christ, charged with representing him in this world, we have a serious responsibility to acknowledge the ministry opportunity God has put before us. Even as Christians confront injustices and oppression—fighting global poverty, sex trafficking, slavery, unfair wages, child labor, environmental exploitation—we need more Christians to be aware of these needs very close to home, affecting many of our own friends and neighbors. This kind of ministry is much less glamorous than those that involve international travel. It may be less rewarding than the ones where you always see tangible results. It may be less enjoyable than helping people who always say thank you. But it is no less important. And it is something every single one of us is called to do. It’s part of loving our neighbors, and we can do this as an expression of our faith and calling.

Seven Ways You Can Minister to Those Suffering from Mental Illness

When my mom’s schizophrenia became impossible to ignore any longer, I had been part of the church for my entire life. In fact, as a pastor’s kid, I had had a front-row seat. I wish I could say the church was an integral part of my healing. While God was the most important part, the church didn’t play that role. Instead, like so many people whose families are disrupted by serious mental illness, I felt the church was a place where our struggle had to be kept out of sight and out of mind.

You don’t have to send that same message to your church. In fact, you have a responsibility to contradict it. Here are seven ways you can help, starting now.

When people seek help for mental illness, they go first to a member of the clergy. Here are 7 ways you can be prepared to help them. Share on X1. Get Past Stigma

With the possible exception of Alzheimer’s disease, all forms of mental illness are plagued by a terrible sense of stigma and shame that accompanies both their symptoms and their diagnosis. People who experience mental health problems are subject to all kinds of judgment—if only they had more faith, ate more nutritiously, prayed more, lived a better life, stopped being so selfish, or simply got over it. They are treated like outcasts, feared, laughed at, or simply ignored. In churches they are singled out for exorcisms, special religious requirements, or exclusion from ministry. Most people show a shocking lack of understanding of mental illness compared to other forms of disorder and disease. You will be on great footing to help people affected by mental illness if you get past this stigma and approach them in the same way you would approach any other person with a significant health problem. If you find you can’t quite get past your fears, hurtful ideas, or impulse to avoid people with mental illness, please pretend you can. Fake it and pray for God to change your heart and your mind.

2. Get Educated

If you do any kind of ministry in a church, you’re on the front lines of mental health care. Most of us are very poorly equipped to offer the help people need, either directly or through appropriate referral. You have a responsibility to educate yourself so you can better understand the needs of a people who will be coming to you for ministry. Some will tell you they’re struggling with mental health; others will not. Your understanding of signs and symptoms and available resources may make the difference between life and death for that person, between a ministry opportunity and a shameful episode for you.

If you do any kind of ministry in a church, you’re on the front lines of mental health care. Get educated. Share on XIf you have mental health professionals and people who openly admit to mental illness in your congregation, ask both to help educate you on various forms of mental illness, a working knowledge of appropriate responses, the differences between various types of mental health professionals, and what people need from the church. Take a one-day training course through Mental Health First Aid. You can also spend a little time on the websites for the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

3. Pray for Them

I hope you already know about the power of prayer to help and heal, and to comfort those who know someone is bringing their concerns before God. But if your church is like most, you never pray publicly for people affected by mental illness. Please pray privately with people who come to you with their needs, please bring them before God in your own prayer time, and please also remember how much it can mean to hear requests lifted up before the congregation. Unless you receive permission from someone to name them publicly, do this in general terms rather than naming names. Chances are, by praying in general for those affected by depression, anxiety disorders, or mental health struggles, you will be engaging in powerful ministry to several people in your congregation.

4. Connect Them

Develop a vetted list of mental health providers and facilities in your area, including hotlines and support groups. Make it widely and conspicuously available. If someone comes to you for help, you’re an important gatekeeper, so prepare yourself to help people access good professional care. And while you’re at it, help them find each other. You probably know other people who have walked through mental health problems and related crises. Or if you don’t already, you will when you make yourself a safe person for people to approach when they’re struggling. Instead of allowing people to persist in their belief that they are alone in their struggle, help them find others who can relate to what they’re walking through. Even better, connect them with people who have already learned to navigate the mental health care system—a huge challenge no one is born equipped for—and may be willing to mentor them as they seek care.

5. Get (or Stay) Close

When people are experiencing any kind of crisis, the last thing they need is for people they rely on to distance themselves. When people are dealing with a mental health problem, they may feel abandonment even more acutely because they’re extra sensitive to rejection, thanks to stigma, and because their emotions can be overwhelming. Resist the impulse to pull away or to believe you are inadequate because you don’t know what to do to help them. You can’t cure cancer either—you’re probably not even qualified to administer chemotherapy—but that probably doesn’t stop you from staying in the lives of people who are diagnosed with it. You do know what to do—be a friend and be a spiritual leader. But don’t forget to exercise healthy boundaries. You are not the complete answer to anyone’s problems. Do what you can and be honest about what you can’t.

6. Give Them Spiritual Assurance

Spiritual crisis nearly always accompanies a mental health crisis. One of the greatest gifts you can give a family in this kind of crisis is assurance that God loves them, he has not walked away from them, he has not abandoned them, and a mental health problem does not indicate they have not done enough for God. Unfortunately, churches often reinforce the opposite message and allow religious legalism to condemn people for their health problems (in a way we would never tolerate in reference to other health problems). Even when church leaders don’t send these messages, their silence can reinforce the shame and self-blame that tends to fill people’s heads. As a representative of God’s love and grace, you have a responsibility to actively contradict these ideas and to remind them how precious they are to God in their suffering.

7. Let Them Do Ministry

You may be tempted to believe that people affected by mental illness can’t serve in the church. But mental illness does not take God by surprise, cancel people’s spiritual gifts, or make a person’s life worthless or even purposeless. God always has a purpose for everyone, and God can and will redeem our most painful experiences for his glory. Refuse to stand in the way of God’s work. When individuals and families are stable and caring for their health, encourage them to serve according to their gifts. And be ready to let them off the hook, without judgment, on the days when they don’t have the capacity to give. This will be a tremendous blessing to your church, and it can provide an important piece of structure and motivation to help a person maintain health.

As a follower of Christ, you represent Christ to suffering people. God draws such people to himself, and they often come to the church looking for help. Please take this responsibility seriously and be the well-equipped, well-informed light that people walking in darkness need.