Commemorating the Uncommon Humility of John Stott

Editor’s Note: Today marks what would have been the 100th birthday of John Stott, renowned author, theologian, and former rector of All Souls Church in London, England; he is widely regarded as one of evangelicalism’s leading thinkers and leaders. To commemorate his birthday, pastor Corey Widmer who also served as one of Stott’s study assistants offers this reflection on Stott’s continuing relevance to evangelicalism today and the reasons why he should be far from forgotten.

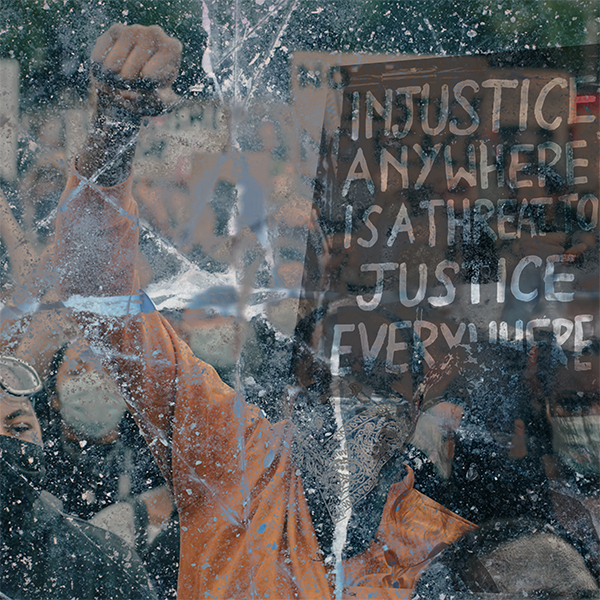

The last twelve months may well be remembered as a defining apocalypse for American evangelicalism, “apocalypse” in the true sense of the term: a revealing, a disclosing, a revelation of the truth of the matter. Just as hydraulic pressure exposes what lies beneath the surface of the ground, the accumulated traumas of the last year have revealed in many ways what is most true about the American evangelical movement. And it’s not been pretty.

Evangelicals are among those who have been most resistant to common-sense pandemic precautions, the most susceptible to political and social conspiracies, the most unwilling to support racial and social justice, and the most prone to capitulate to political and theological syncretism. It is now well-documented that the January 6th insurrection was enabled in part by self-identifying evangelical populists. Recent incidents such as the senseless murder of Asian women in Atlanta as well as the seemingly unrelenting moral failures of prominent evangelical male leaders have revealed the dangerously shallow forms of discipleship that shape evangelical culture. It is no surprise that young adults and people of color are vocally departing evangelical churches and institutions,1 exhausted by the combative posture, the lack of social vision, and the entrenchment in white-majority cultural perspectives and traditions.

What’s the future of American evangelicalism? What does the label “evangelical” even mean anymore, and is it worth preserving? Who are the leaders who can help attend to these underlying maladies and bring healing and renewal?

The answers to these questions aren’t clear. But on the 100th anniversary of John Stott’s birthday and the 10-year anniversary of his death, I’d like to propose that he remains an important voice for the evangelical movement to remember and consider, even as we need to continue to broaden the scope of those whose voices are regarded and included in guiding evangelicalism forward.

“Who is John Stott?” So ran the title of an op-ed by David Brooks in the New York Times in 2004. In that piece, Brooks suggested that while the media at the time was occupied with the foibles of prominent evangelicals like Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, they should instead be focusing on Stott as a truer reflection of evangelicalism. Quoting the late Michael Cromartie, Brooks wrote, “If evangelicals could elect a pope, Stott is the person they would likely choose.”

Many younger American Christians would still likely ask Brooks’s question, “Who is John Stott?” I was not personally very familiar with Stott before I moved to London in 1999 to work as his “study assistant.” I remembered seeing his book Basic Christianity prominently displayed at the Urbana Student Missions Conference and hearing of his impact there as the longest-running Bible teacher. I knew that he was considered one of the superlative preachers of the 20th century. But until I worked for him and began to understand his legacy, I did not grasp the unique quality of his leadership and how important it was for modern-day evangelicalism.

Until I worked for John Stott and began to understand his legacy, I did not grasp the unique quality of his leadership and how important it was for modern-day evangelicalism. Share on XOne of Stott’s enduring concerns was to distance evangelicalism from fundamentalism. One of the last books he wrote is called Evangelical Truth in which he stated that “this is how I would wish to be remembered and judged.” The book clarified what he believed to be the essentials of what makes evangelicalism distinct in contrast to fundamentalism on the one hand and liberalism on the other. But he was especially keen to distance evangelicalism from the tendencies of fundamentalism, which he viewed as dangerous to the gospel. Among these tendencies he included: 1) a distrust of scholarship and science; 2) a refusal to repent of white supremacy; 3) a resistance to social responsibility, and 4) social separatism. Reading this twenty years later, it’s clear that at least in the American evangelical movement, the specter of fundamentalism continues to haunt our halls.

In contrast to fundamentalism, Stott modeled a robust evangelicalism that engaged deeply with the great public issues of his time, while maintaining a radical Christ-centeredness and commitment to the authority of Scripture. In addition to his many books on the Bible and other theological topics, he researched and wrote extensively about current ethical issues, ranging from nuclear disarmament to sexuality and gender. He paired his passion and practice of evangelism with an ardent commitment to social justice, writing that “[t]he cross is a revelation of God’s justice as well as his love. That is why the community of the cross should concern itself with social justice as well as with loving philanthropy.”2 Among evangelicals he was an early proponent of women’s ordination and leadership in the church, skillfully defending gender equality from Scripture. He had a deep respect for the scientific community and was one of the first prominent evangelicals to support a theistic evolutionary creation account. He had a passion for creation care, which went far beyond his own personal hobby of birdwatching to include advocacy for environmental stewardship of vulnerable species and habitats.3 And yet more than anything else, his supreme concern remained the glory and exaltation of Jesus as Lord. On his gray slate gravestone in a tiny village graveyard in southwest Wales, his epitaph simply states:

Buried here are the ashes of John Stott, who resolved both as the ground of his salvation and as the subject of his ministry to know nothing except Jesus Christ and him crucified.

In contrast to fundamentalism, Stott modeled a robust evangelicalism that engaged deeply with the great public issues of his time, while maintaining a radical Christ-centeredness and commitment to the authority of Scripture. Share on X

Recently I spoke with Mark Labberton, another former study assistant of Stott’s and the current president of Fuller Seminary. I asked Mark, “How do you think John became the thinker and leader that he was, modeling such a balanced form of evangelicalism in such polarizing conditions?” Mark’s first response was his “cultural humility.” Raised in the privilege of London’s West End, it was Stott’s destiny to inherit a British colonialist worldview and climb the ranks of elite society. Instead, Stott spent much of the second half of his life traveling around the world to serve the global church, listening to and learning from those outside his social location.

One particularly important relationship that Stott developed was with René Padilla, a prominent Ecuadorian theologian and church leader in Latin America. On one occasion John and René, along with Latin American theologians Orlando Costas and José Míguez Bonino, were driving through the rural countryside of Costa Rica in an old pickup truck. They were debating the efficacy of Marxism versus capitalism, and the compatibility of each with Christianity. As they navigated the narrow road, the four men stopped to watch a group of peasants plow a hillside field. Stott later wrote in his diary that this experience of hearing the perspectives of his Latin American colleagues along with encountering the poverty of the Global South and seeing it in the backdrop of political corruption deeply moved him and challenged his Western understanding of the gospel. Padilla often commented on how disorienting it was to see an upper-crust British leader demonstrate such uncommon humility, exhibited in his desire to genuinely understand the perspectives of those in the majority church and to integrate them into his own.

Stott not only listened—he put his learning into action. In 1974, Padilla and Stott were both in attendance at the Lausanne International Congress on World Evangelization, which at the time was the largest and most diverse gathering of Christians in history, convened around a commitment to carry out the Great Commission. Stott served as the chairman of the drafting committee for the Lausanne Covenant, the defining document produced from the Congress. While the powerful North American representatives lobbied hard for a narrow interpretation of missions centering on evangelism, representatives of the Global South led prominently by René Padilla cried out for a broader understanding of missions that included social justice, poverty alleviation, and a repudiation of Western paternalism. In a famous standoff, Stott disagreed publicly with Billy Graham and other Western colleagues and sided with the Majority-World church leaders, ultimately winning the Congress over through his unparalleled powers of communication and biblical exposition. The legacy of Lausanne would be very different were it not for Padilla and Stott’s friendship and partnership.

In a famous standoff, Stott disagreed publicly with Billy Graham...and sided with the Majority-World church leaders, ultimately winning the Lausanne Congress over through his unparalleled powers of communication and biblical exposition. Share on XOver the last year, I’ve often wondered what “Uncle John,” as those close to him called him, would say and do in response to the current crisis in evangelicalism. But given his writings and record, I think we could venture a guess. I’m quite sure he would call us to “evangelical repentance,” as he did so in his opening address at the Lausanne Congress. He would invite us to repent of our:

- Preoccupation with success and personality-based ministry, a dangerous path that so often leads to moral disaster.

- Tribalism and intellectual shallowness, which fail to acknowledge the common grace and truth at work in the world around us.

- Pursuit of political and cultural power, accepting instead humiliation and marginalization as a way of identifying with Jesus and the global church.

- Cultural superiority and invite us to listen to and learn from our brothers and sisters who have been historically marginalized and oppressed.

And he would invite all of us to go the way of the cross, embracing “a death to sin through identification with Christ, a death to self as we follow Christ, a death to ambition in cross-cultural mission, a death to security in the experience of persecution and one of martyrdom, and death to this world as we prepare for our final destiny.”4

I’m not sure what the future of evangelicalism holds. But as we try to find our footing, there is hardly a better posthumous guide for our community than John Stott. Today, on what would have been his 100th birthday, let’s not just celebrate this incomparable Christ-like leader; let’s remember his forward-thinking influence as we envision the future of this movement. Stott’s version of a culturally-humble, socially-engaged, world-affirming, and Christ-centered evangelicalism is one that I, along with many others, would be excited to embrace.

[1] For example, see the “Leave Loud” campaign.

[2] John Stott, The Cross of Christ (Downers Grove: IVP, 1986), 292.

[3] See “For the Love of the World: John Stott and His Passion for Creation“.

[4] John Stott, The Radical Disciple (Downers Grove: IVP, 2010), 133.