Informed But Not Transformed: The Power of Art in Our Formation (Pt. 2)

The Arts as an Avenue for Spiritual Renewal in Teenagers

If you ever want to have a great conversation with a high school student, spend some time with them as they’re doing something they are passionate about. Some of my best conversations with students have come on the sideline of a soccer field, fishing, playing music, or in the middle of an art project. It’s easier to share ourselves with others when we feel fully alive.

I recently sat across the table from a high school junior following our student band rehearsal. Emmy is a talented guitar player, and one of our long-time student leaders, but she’d begun to feel frustrated with where she was in her faith journey. She articulated:

“I feel like I’m doing all the right things, but I feel distant from God. What can I do?”

As students are inclined to do, she answered her own question:

“I wonder if getting to know God is more like learning to play guitar than learning in school. When you’re learning an instrument you can’t learn fast – like you do when you cram for a test (and then promptly forget it all) – you just keep doing it. Then you try playing with people, and over time it just sticks.”

Review: The Banking System of Education

I reflected in Part 1 on what educational researcher bell hooks describes as the “banking system of education,”1 and its potentially damaging impact on how we view discipleship to teenagers. Core to hooks’ critique is the suggestion that the systems we develop have the capacity to incentivize passive learning, rewarding achievement (such as internalization of the information needed to pass a test) over true transformation. My suggestion in that first piece is that the same risk present in the education system exists in our student discipleship spaces. As my friend Emmy articulates so eloquently, learning all the right things, or even doing all the right things doesn’t necessarily lead to transformation. Transformation comes as we do the long hard work of living out what we have received. Historically in the Christian church, this has been found within the role of spiritual practice.2

The systems we develop have the capacity to incentivize passive learning, rewarding achievement (such as internalization of the information needed to pass a test) over true transformation. Share on X

The Role of Art in Our Spiritual Renewal

I share the anecdote above because I think my friend might have named one of the necessary balances churches may need to find to counter the influence of the “banking system of education:” The role of art in our spiritual renewal. This is not a new thought. The church has a long history of using the arts as an on-ramp to spiritual practice. I will make a case for how a revival of spiritual exploration through the arts might serve as a uniquely powerful antidote to those hoping to guide young people into deeper relationship with Christ in a world that prioritizes achievement over almost anything else.

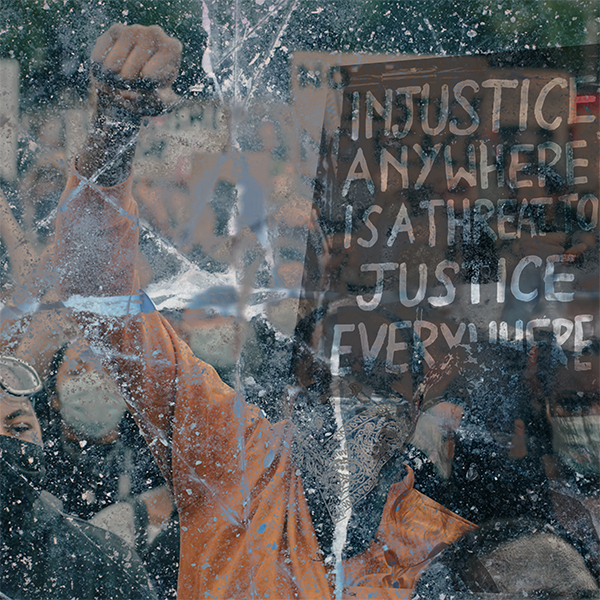

I am an artist, and I come from a long line of artists. In my journey as an artist, I’ve found the arts to be an invaluable tool for truth-telling, spiritual reflection, and depth of formation. This can be true well outside the realm of the Christian faith. Storytelling through artistic means is not the sole purview of the Christian faithful. However, one of the powers of the arts is its capacity to give language to the complexity of the human experience – which is of course an aim of the Christian faith as well. Art across the centuries has served as a language giving voice to lament, grappling with the tragedy and loss of war, wondering at the beauty of the created order, and inviting others to sit in the tension of our own lived experience.

For example, the above painting is Pablo Picasso’s acclaimed work, Guernica.3 Guernica is Picasso’s own reflection on the destruction and confusion of war. In it, he invites the world to sit with him in the horror and pain he felt in the midst of the atrocities of the Spanish Civil War. It’s an example of Picasso speaking truthfully about the pain and chaos of his lived experience.

A pastor at our church recently started his message by giving a tub of Play-Doh to every student in our middle school ministry. His charge? Make something that represents you. His challenge was simple and open-ended: students were invited in their own playful way to created something that describes themselves. As they worked, he shared a message on Ephesians 2:10, reminding students that they are God’s handiwork, intentionally created by a God who loves them. This simple act of making, in conjunction with traditional Scriptural teaching, opened the doors for students to speak honestly about themselves. They wrestled with vulnerability about the ways they felt confident and self-conscious. Students spoke in their own language about their wrestling with identity, particularly in regard to their understanding of God. For an hour that night, art was a shared language that helped our students to grapple meaningfully with their identity and to do so in community.

One of the student Play-Doh creations from a recent message on how students are God’s handiwork.

As we create, we have an opportunity through the reflective power of the arts to hold up a picture of the world as we honestly see it, grappling with both the good and the bad that we experience.

The arts has capacity to give language to the complexity of the human experience – which is of course an aim of the Christian faith as well. (1/2) Share on X

Art across the centuries has served as a language giving voice to lament, grappling with the tragedy of war, wondering at the beauty of the created order, and inviting others to sit in the tension of our own lived experience. (2/2) Share on X

Literature: Word Pictures of the World

Literature can be particularly helpful in this way. Claude Atcho elaborates this truth in his powerful work, Reading Black Books: How African American Literature Can Make Our Faith More Whole and Just, writing:

“To read literature is to incarnate and inhibit the experience of another, as crafted by the author. Literature’s empathic power is why abolitionists leveraged slave narratives to warm the cold consciences of northerners indifferent to the suffering of enslaved Black persons. To read literature is to experience…a powerful bond of empathy.”4

This is the genius of great authors of literature. They invite us to inhabit worlds, to see injustice up close, and to react against it. Atcho uses the example of Richard Wright’s classic Native Son. He writes, “To read Richard Wright’s Native Son with empathy is to put yourself in Bigger Thomas’s traumatized existence, walking hundreds of pages in his protagonist shoes.”5 Such an endeavor would be meaningful in itself, but Atcho suggests Christians engaging with the art of story have an opportunity to take reflection one step further, reading literature in light of the Gospel. Atcho continues: “To read Native Son theologically is to do one better; it’s to walk farther in Bigger’s shoes, not ending our journey once we reach the road to empathy but seeking to reach the road to Emmaus, finding the intersection between the story of Bigger and the story of Jesus.”6

We have an opportunity to invite our young people to be both readers and writers of great stories. We can be a Church that celebrates the art of storytelling and sits intentionally in the presence of others’ stories, seeing as they intersect with the bigger story of Jesus, empathizing and growing from them. As we do this, our faith will be richer, and our students will be better equipped to engage authentically with the world.

This is the genius of great authors of literature. They invite us to inhabit worlds, to see injustice up close, and to react against it. Share on X

The Act of Making

Tish Harrison Warren writes of the act of making as one of longing and lament. In our act of creation, we grapple with the brokenness of our world but also reach for the eternity written on our hearts. We join God in making all things new. Warren writes:

“The act of labor and artmaking – as terrible as it feels at times – is an attempt to grasp the ineffable and transcendent. It is an ordinary way that we reach toward beauty and glory, a way of reaching toward the eschaton, the place (or time or dimension) of beauty and glory. Every note on a guitar or delicious turn of phrase or quilt quilted is part of Jesus’ work in making all things new…As Christians, our acts of making are an embodied proclamation that the curses of Genesis 3 are not the final word… Art making calls forth the future, rendering the eschaton present in the here and now.”7

Alastair Gordon describes this act of making as cleaning windows in the new creation. He writes:

“There is a home for us that is being prepared by the risen Lord Jesus. It has many rooms and is closer than we think. Art matters because it wipes away the dirt so that we might peer through the windows and see the wonder inside. The goodness of God leaks through from the new creation. Our task is to polish the mirrors and clean the windows.”8

When we create spaces through the arts for our young people to grapple with who they are and how they see the world, we change the playing field. The arts invite students to stand before the world honestly and look forward to its (and our) restoration.

In our act of creation, we grapple with the brokenness of our world but also reach for the eternity written on our hearts. We join God in making all things new. Share on X

The Arts as a Counter-Liturgy to Immediacy

Finally, the arts provide a counter-liturgy to rhythms of busyness and immediacy that so permeate our communities. While sharing a version of ourselves on social media is quick and easy, the pain comes in the long wait for the feedback of peers and strangers on the other end of our iPhones. Jean Twenge describes the measurable increase in anxiety and depression among teenagers who fail to get a reply to a text or social media message, or who fail to get the digital response expected on social posts.9 The act of making flips this equation. It can be quick to post on social media, and painful once the post is in the world. Conversely, the act of making can be painstaking and slow, but immensely gratifying once it is completed.

Tish Harrison Warren reflects, in the same essay quoted previously, about the long arduous painful act of writing, and the joy of having written.10 Makoto Fujimura writes similarly of the painstaking action of making:

“Art does not come easy: this sacred, God-given impulse…both ‘doing’ and ‘becoming a poem.’ It is hard work to live into this generative love, and it is what we are made for: to paint light into darkness, to sing in co-creation, to take flight in abundance.”11

As we invite our students to explore themselves through the arts – to wonder about who they are and their place in the world – we invite them into something that is inherently difficult. It is immensely hard to create, but it is gratifying. And in creating, we join our creative Savior in bringing forth the beauty Jesus has made in the world. Michelangelo famously declared his statues had always been present in the rock, and that he’d simply “chiseled away the superfluous material.”12Alastair Gordon suggests our act of creation is similar. He writes “If the role of the artist is to bring forth new works of God’s creation, perhaps our task is similar to that of Michelangelo: to find what God has made and reveal it to the world. It’s a bit like children at Christmas unwrapping the presents under the tree.”13 As we invite our young people to engage with the arts as an avenue for spiritual formation, we invite them to take an earnest and lengthy look at the world and themselves and bring forth the good that God has made. It will be hard, and it will be healing.

When we use art as a model for spiritual formation, we are invited to slow down enough to reflect on the mystery of God and find comfort in our limited understanding of the world. Art gives voice to young people and invites them to help bring change into the world, putting their faith into action. Art helps us to slowly bring the hope of the gospel into our world.

///

Formational Artistic Practices

Here are a few artistic practices you might try to supplement your own formational journey, and help the young people in your life practically grapple with their faith.

- Lectio Divina. Rather than teaching about scripture, create space for young people to bathe in the words of God. It’s one thing to know that God is with us, it’s another to rest in the presence of the Good Shepherd of Psalm 23.

- Write Music or Poetry. Music and poetry give voice to name the brokenness we see in the world and speak with hope of its restoration.14

- Paint or Draw the Beauty in the World. Drawing is slow, laborious work. Drawing the beauty in the world gives us space to sit and reflect on the majesty of God’s creation. We sit in the presence of his beauty and bring it forth to our communities.

- Invite Students to use Creative Gifts to Craft Liturgy. Whether it’s their music, graphics, or video creation, invite young people to participate in the work of the people of God practically and fully!

Below are a few of my own pieces corresponding to the practices above.

Lectio Divina | Psalm 23 with original art | © Steve Noble

Original Poem | Reflecting on the exodus and the brokenness in the world, with original artwork. | © Steve Noble

The arts provide a counter-liturgy to rhythms of busyness and immediacy that so permeate our communities. The act of making can be painstaking and slow, but immensely gratifying once it is completed. Share on X

///

Bibliography, Part 2

- Atcho, Claude. Reading Black Books: How African American Literature Can Make Our Faith More Whole and Just. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Brazos Press, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2022.

- Barbeau, Jeffrey W., and Emily Hunter McGowin, eds. God and Wonder: Theology, Imagination, and the Arts. Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, 2022.

- Fujimura, Makoto. Art and Faith: A Theology of Making. New Haven ; London: Yale University Press, 2020.

- Gordon, Alastair. Why Art Matters A Call for Christians to Create. London: IVP, 2021.

- hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge, 1994.

- Picasso, Pablo. Guernica. 1937. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía.https://www.museoreinasofia.es/coleccion/obra/guernica.

- Twenge, Jean M. IGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy?: And Completely Unprepared for Adulthood: And What That Means for the Rest of Us. New York: Atria Books, 2018.

- Watkins, Ralph C. Hip-Hop Redemption: Finding God in the Rhythm and the Rhyme. Engaging Culture. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic, 2011.

Footnotes

1 hooks, 203.

2 For more on this see Part 1 of my series, “Informed, But Not Transformed: Critiquing the Banking System of Education.”

3 Picasso, Pablo. Guernica. 1937. Accessed at https://www.pablopicasso.org/guernica.jsp.

4 Atcho, Claude. Reading Black Books: How African American Literature Can Make Our Faith More Whole and Just. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Brazos Press, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2022, 2.

5 Ibid., 2.

6 Ibid., 2.

7 Tish Harrison Warren, writing in Barbeau and McGowan, 60.

8 Gordon, 68.

9 Twenge, 105.

10 Warren, writing in Barbeau and McGowan, 64.

11 Fujimura, 14.

12 Quoted in Gordon, 52.

13 Gordon, 52.

13 Watkins, 85.